ALENKA V ŘÍŠI DIVŮ

5

CHAPTER V.

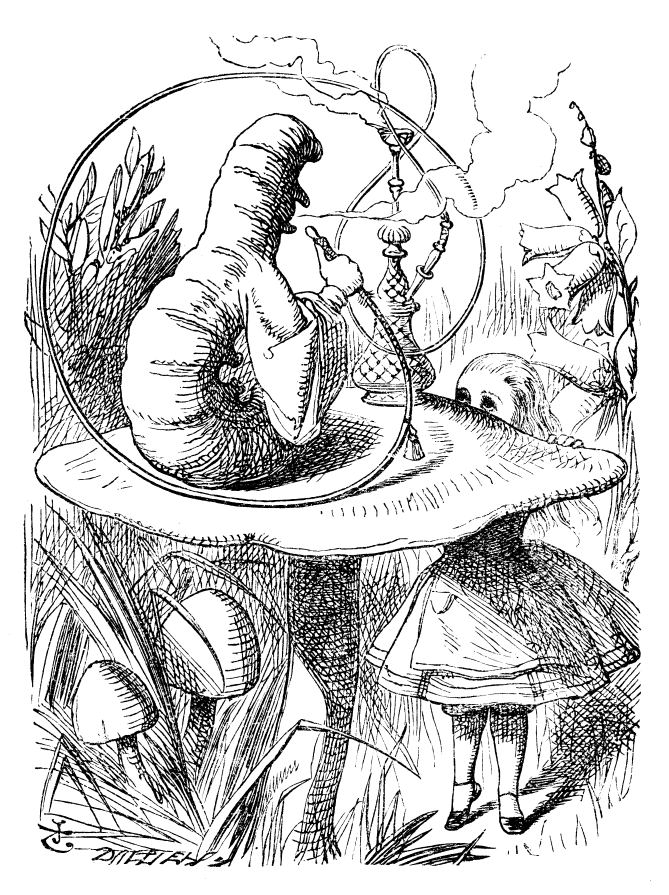

NA RADU U HOUSENKY

Advice from a Caterpillar

Housenka s Alenkou se na sebe chvíli dlívaly mlčky, konečněvyňala Housenka dýmku z úst a oslovila Alenku mdlým, ospalým hlasem.

The Caterpillar and Alice looked at each other for some time in silence: at last the Caterpillar took the hookah out of its mouth, and addressed her in a languid, sleepy voice.

"Kdo jste?" řekla Housenka.

'Who are YOU?' said the Caterpillar.

Takovéhle oslovení k hovoru zrovna nepovzbuzovalo. Alenka odpověděla poněkud zaraženě: "Já - já - ani sama v tomto okamžiku nevím - totiž vím, kdo jsem byla, když jsem dnes ráno vstávala, ale od té doby jsem se, myslím, několikrát musila proměnit."

This was not an encouraging opening for a conversation. Alice replied, rather shyly, 'I — I hardly know, sir, just at present—at least I know who I WAS when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.'

"Co tím chcete říci?" řekla Housenka přísně. "Vysvětlete to svými slovy!"

'What do you mean by that?' said the Caterpillar sternly. 'Explain yourself!'

"Ale když to svými slovy nemohu, paní Housenko," řekla Alenka, "protože já nejsem já, rozumíte?"

'I can't explain MYSELF, I'm afraid, sir' said Alice, 'because I'm not myself, you see.'

"Nerozumím," řekla Housenka.

'I don't see,' said the Caterpillar.

"Obávám se, že to jasněji povědět nedovedu," odvětila Alenka velmi zdvořile, "neboťtomu za prvé sama nerozumím; a tak hle projít v jednom dni tolika různými velikostmi, to člověka strašnězmate."

'I'm afraid I can't put it more clearly,' Alice replied very politely, 'for I can't understand it myself to begin with; and being so many different sizes in a day is very confusing.'

"Nezmate," řekla Housenka.

'It isn't,' said the Caterpillar.

"No, snad jste to ještěnezkusila," řekla Alenka; "ale až se budete mít zakuklit - a to budete jednou muset - a pak se z kukly proměnit v motýla, tak si myslím, že se vám to bude také zdát trochu podivné, ne?"

'Well, perhaps you haven't found it so yet,' said Alice; 'but when you have to turn into a chrysalis—you will some day, you know—and then after that into a butterfly, I should think you'll feel it a little queer, won't you?'

"Ani dost málo," řekla Housenka.

'Not a bit,' said the Caterpillar.

"Nu, vy to tedy snad berete jinak," řekla Alenka; "já vím jen tolik, pro mne že by tobyl velmi podivný pocit."

'Well, perhaps your feelings may be different,' said Alice; 'all I know is, it would feel very queer to ME.'

"Pro vás!" řekla Housenka pohrdavě. "Kdo vůbec jste?"

'You!' said the Caterpillar contemptuously. 'Who are YOU?'

Což je přivedlo zas tam, kde byly, když začaly. Alenku trochu popuzovalo, že Housenka dělá tak velmi úsečné poznámky - postavila se tedy zpříma a řekla velmi vážně: "Myslím, že je na vás, abyste mi napřed řekla, kdo jste vy."

Which brought them back again to the beginning of the conversation. Alice felt a little irritated at the Caterpillar's making such VERY short remarks, and she drew herself up and said, very gravely, 'I think, you ought to tell me who YOU are, first.'

"Proč?" řekla Housenka.

'Why?' said the Caterpillar.

To byl nový hlavolam; a jelikož Alenka nedovedla nalézti vhodnou odpověďa Housenka se zdála být ve velmi nepříjemné náladě, obrátila se k odchodu.

Here was another puzzling question; and as Alice could not think of any good reason, and as the Caterpillar seemed to be in a VERY unpleasant state of mind, she turned away.

"Vraťte se!" zavolala za ní Housenka. "Mám vám něco důležitého říci!"

'Come back!' the Caterpillar called after her. 'I've something important to say!'

To znělo slibně: Alenka se obrátila a šla zpět.

This sounded promising, certainly: Alice turned and came back again.

"Nerozčilujte se," řekla Housenka.

'Keep your temper,' said the Caterpillar.

"A to je všechno?" řekla Alenka, potlačujíc svůj hněv, jak nejlépe dovedla.

'Is that all?' said Alice, swallowing down her anger as well as she could.

"Ne," řekla Housenka.

'No,' said the Caterpillar.

Alenka si pomyslila, že vlastněnemá co dělat a že tedy může počkat; snad nakonec přece jen uslyší něco, co bude stát za poslechnutí. Housenka nějakou chvíli bafala z dýmky a neříkala nic; konečněvšak rozdělala založené ruce, vyňala dýmku z úst a řekla: "Tak vy si tedy myslíte, že jste se proměnila, není-liž pravda?"

Alice thought she might as well wait, as she had nothing else to do, and perhaps after all it might tell her something worth hearing. For some minutes it puffed away without speaking, but at last it unfolded its arms, took the hookah out of its mouth again, and said, 'So you think you're changed, do you?'

"Obávám se, že ano," řekla Alenka; "nepamatuji si věci jako jindy - a ani deset minut nedovedu zůstat stejněvelká!"

'I'm afraid I am, sir,' said Alice; 'I can't remember things as I used—and I don't keep the same size for ten minutes together!'

"Nepamatujete si jaké věci?" řekla Housenka.

'Can't remember WHAT things?' said the Caterpillar.

"Nu, zkoušela jsem říkat Běžel zajíc kolem plotu a odříkávala jsem něco docela jiného!" odvětila Alenka smutně.

'Well, I've tried to say "HOW DOTH THE LITTLE BUSY BEE," but it all came different!' Alice replied in a very melancholy voice.

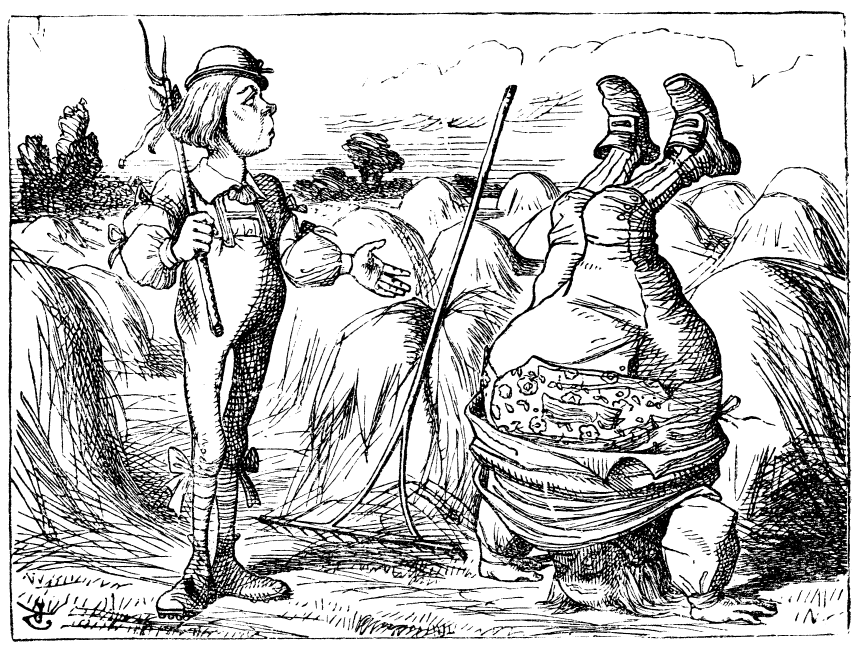

"Tak mi odříkejte Večer před svatým Janem," řekla Housenka.

'Repeat, "YOU ARE OLD, FATHER WILLIAM,"' said the Caterpillar.

Alenka složila způsobně ruce a začala:

Alice folded her hands, and began:—

"Večer před svatým Janem

hovoří syn s Tomanem:

,Jste už stár, váš vlas je bílý,

a přec ještěkaždou chvíli

na hlavěvás vidím stát.

Myslíte, ve vašem stáří

že je zdrávo hospodáři,

aby tenhle sport měl rád?`

'You are old, Father William,' the young man said,

'And your hair has become very white;

And yet you incessantly stand on your head—

Do you think, at your age, it is right?'

, Ve svém mládí, ` Toman vece,

,strach jsem měl, že by tím přece

sportem mozek újmu vzal.

Zjistiv však, na místo mozku

že mám hlavu plnou vosku,

stojky stavím dál a dál. `

'In my youth,' Father William replied to his son,

'I feared it might injure the brain;

But, now that I'm perfectly sure I have none,

Why, I do it again and again.'

, Ve svém stáří, ` vece mladý,

,netrpíte jistěhlady;

ztloustl jste po celém těle.

Myslíte, ve vašem věku

že se dožijete vděku,

kozelce metaje smělé?`

'You are old,' said the youth, 'as I mentioned before,

And have grown most uncommonly fat;

Yet you turned a back-somersault in at the door—

Pray, what is the reason of that?'

,Pročbych pochybou těmučil?`

mudřec dí, ,v mládí jsem učil

touto mastí svoje oudy

pružnosti: Kup! drahá není,

učiníš mi potěšení,

uživ rozkoší těch proudy. `

'In my youth,' said the sage, as he shook his grey locks,

'I kept all my limbs very supple

By the use of this ointment—one shilling the box—

Allow me to sell you a couple?'

Dí syn: ,Stár jste, já jsem mladší,

člověk by řek, že vám stačí

zuby tak na prosnou kaší

nebo měkkou buchtu s mákem.

Jak, že s kostmi, se zobákem

slup jste celou husu naši?`

'You are old,' said the youth, 'and your jaws are too weak

For anything tougher than suet;

Yet you finished the goose, with the bones and the beak—

Pray how did you manage to do it?'

, V mládí studoval jsem práva, `

Toman dí, ,kde vlastní hlava

nepronikla změtí záhad,

s ženou jsem věc prohádat.

Tento cvik jurisprudence

prospěl mněi mojí Lence:

odučil nás oba váhat

a mněsílu v čelist dal. `

'In my youth,' said his father, 'I took to the law,

And argued each case with my wife;

And the muscular strength, which it gave to my jaw,

Has lasted the rest of my life.'

,Stár jste, ` dí syn, ,hrbíte se,

celé tělo se vám třese

dole, ba i nahoře.

Čím to, na nosu že špici

dovedete jako svíci

balancovat úhoře?`

'You are old,' said the youth, 'one would hardly suppose

That your eye was as steady as ever;

Yet you balanced an eel on the end of your nose—

What made you so awfully clever?'

Otec Toman smračil čelo

a promluvil neveselo:

,Otázek jsem do třetice

zodpověděl, to je dosti.

Nedost-li tvé zvědavosti,

vykopnu těze světnice.`"

'I have answered three questions, and that is enough,'

Said his father; 'don't give yourself airs!

Do you think I can listen all day to such stuff?

Be off, or I'll kick you down stairs!'

"To nebylo správně," řekla Housenka.

'That is not said right,' said the Caterpillar.

"Ne zcela správně, obávám se," řekla Alenka zaraženě. "Některá slova se změnila."

'Not QUITE right, I'm afraid,' said Alice, timidly; 'some of the words have got altered.'

"Bylo to špatněod začátku do konce," řekla Housenka rozhodně, a několik minut bylo ticho.

'It is wrong from beginning to end,' said the Caterpillar decidedly, and there was silence for some minutes.

Housenka opět promluvila první.

The Caterpillar was the first to speak.

"Jak veliká chcete být?" zeptala se.

'What size do you want to be?' it asked.

"Ó, co se týče velikosti, na tom by mi tolik nezáleželo," odpověděla Alenka spěšně; "jen se mi nelíbí to stálé měněni, víte."

'Oh, I'm not particular as to size,' Alice hastily replied; 'only one doesn't like changing so often, you know.'

"Nevím," řekla Housenka.

'I DON'T know,' said the Caterpillar.

Alenka neřekla nic. Nikdy v životějí předtím nikdo tolik neodporoval a ona cítila, že ztrácí trpělivost.

Alice said nothing: she had never been so much contradicted in her life before, and she felt that she was losing her temper.

"Jste spokojena teď?" ptala se Housenka.

'Are you content now?' said the Caterpillar.

"Nu, raději bych byla trochu větší, paní, není-li vám to proti mysli," řekla Alenka, "tři palce je taková hloupá výška."

'Well, I should like to be a LITTLE larger, sir, if you wouldn't mind,' said Alice: 'three inches is such a wretched height to be.'

"Tři palce je velmi dobrá výška," řekla Housenka hněvivě, vztyčujíc se (byla přesnětři palce dlouhá).

'It is a very good height indeed!' said the Caterpillar angrily, rearing itself upright as it spoke (it was exactly three inches high).

"Ale já na ni nejsem zvyklá!" hájila se ubohá Alenka žalostným hlasem. A pro sebe si pomyslila: "Kéž by se tato zvířátka tak snadno neurážela!"

'But I'm not used to it!' pleaded poor Alice in a piteous tone. And she thought of herself, 'I wish the creatures wouldn't be so easily offended!'

"Časem si na to zvyknete," řekla Housenka, strčila dýmku do úst a začala opět kouřit.

'You'll get used to it in time,' said the Caterpillar; and it put the hookah into its mouth and began smoking again.

Tentokrát Alenka čekala trpělivě, až se Housence opět uráčilo promluvit. Za nějakou minutu nebo dvěvyňala Housenka dýmku z úst, jednou nebo dvakrát zívla a otřásla se. Pak slezla z hřibu a odplazila se do trávy, poznamenávajícjen jako mimochodem: "Jedna strana vás natáhne, druhá strana vás zkrátí."

This time Alice waited patiently until it chose to speak again. In a minute or two the Caterpillar took the hookah out of its mouth and yawned once or twice, and shook itself. Then it got down off the mushroom, and crawled away in the grass, merely remarking as it went, 'One side will make you grow taller, and the other side will make you grow shorter.'

"Jedna strana čeho? Druhá strana čeho?" pomyslila si Alenka.

'One side of WHAT? The other side of WHAT?' thought Alice to herself.

"Hřibu," řekla Housenka, docela jako kdyby se byla Alenka zeptala nahlas; a v okamžiku byla z dohledu.

'Of the mushroom,' said the Caterpillar, just as if she had asked it aloud; and in another moment it was out of sight.

Alenka se zamyšlenězadívala na hřib uvažujíc, které jsou ty jeho dvěstrany; a ježto byl úplněkulatý, bylo to velmi nesnadno rozhodnouti. Nakonec však roztáhla ruce, objala hřib jak daleko mohla, a každou rukou ulomila kousek okraje jeho klobouku.

Alice remained looking thoughtfully at the mushroom for a minute, trying to make out which were the two sides of it; and as it was perfectly round, she found this a very difficult question. However, at last she stretched her arms round it as far as they would go, and broke off a bit of the edge with each hand.

"A teďkterá je která?" řekla si k soběa uzobla malinký kousekúlomku, který držela v pravé ruce, aby viděla, co se stane; v následujícím okamžiku pocítila prudkou ránu do brady a vrazila bradou do koleni.

'And now which is which?' she said to herself, and nibbled a little of the right-hand bit to try the effect: the next moment she felt a violent blow underneath her chin: it had struck her foot!

Tato náhlá změna ji velmi polekala a Alenka si uvědomila, že nesmí ztratit ani chvíli, nechce-li se zkrátit v úplné nic; tak se ihned dala do práce, aby snědla kousek úlomku z levé ruky. Bradu měla přitisknutu tak těsněke kolenům, že jí skoro nezbývalo místa, aby otevřela ústa; konečněse jí to však podařilo a ona spolkla ždibeček úlomku z levé ruky.

She was a good deal frightened by this very sudden change, but she felt that there was no time to be lost, as she was shrinking rapidly; so she set to work at once to eat some of the other bit. Her chin was pressed so closely against her foot, that there was hardly room to open her mouth; but she did it at last, and managed to swallow a morsel of the lefthand bit.

"Tak konečněmám volnou hlavu!" řekla Alenka s velkým uspokojením; to se však za okamžik změnilo ve zděšení, když shledala, že nevidísvých ramen: vše, co viděla, když pohlédla dolů, byla nesmírná délka krku, který se zdál vyrůstati jako stéblo z moře zeleného listí, rostoucího hluboko pod ní.

'Come, my head's free at last!' said Alice in a tone of delight, which changed into alarm in another moment, when she found that her shoulders were nowhere to be found: all she could see, when she looked down, was an immense length of neck, which seemed to rise like a stalk out of a sea of green leaves that lay far below her.

"Co může být všechna ta zeleň?" řekla Alenka. "A kam se jen poděla má ramena? A - ó, mé ubohé ruce, jak se to stalo, že vás nevidím?" Pohybovala rukama, jak mluvila, ale neviděla žádného účinku, leda nepatrné chvění ve vzdáleném zeleném listí.

'What CAN all that green stuff be?' said Alice. 'And where HAVE my shoulders got to? And oh, my poor hands, how is it I can't see you?' She was moving them about as she spoke, but no result seemed to follow, except a little shaking among the distant green leaves.

Ježto se nezdálo, že se jí podaří dosáhnouti si rukama k hlavě, pokusila se dostati sehlavou k rukám a s potěšením shledala, že může svůj dlouhý krk ohýbati na všechny strany jako had. Zrovna se jí podařilo prohnouti jej v elegantní oblouk a chystala se ponořiti hlavu do zeleně- která, jak shledala, nebyla nic jiného než vrcholky stromů, pod kterými se byla procházela když uslyšela ostré syknutí, které ji přinutilo, aby spěšněuhnula: velký holub jí vlétl do tváře a bil ji zuřivěsvými křídly.

As there seemed to be no chance of getting her hands up to her head, she tried to get her head down to them, and was delighted to find that her neck would bend about easily in any direction, like a serpent. She had just succeeded in curving it down into a graceful zigzag, and was going to dive in among the leaves, which she found to be nothing but the tops of the trees under which she had been wandering, when a sharp hiss made her draw back in a hurry: a large pigeon had flown into her face, and was beating her violently with its wings.

"Had!" křičel Holub.

'Serpent!' screamed the Pigeon.

"Já nejsem had," řekla Alenka uraženě, "dejte mi pokoj!"

'I'm NOT a serpent!' said Alice indignantly. 'Let me alone!'

"Had, pravím znovu!" opětoval Holub, ale již tišeji, a dodal s jakýmsi vzlyknutím: "Zkoušel jsem to na všechny způsoby a nic se jim nezdá vyhovovati!"

'Serpent, I say again!' repeated the Pigeon, but in a more subdued tone, and added with a kind of sob, 'I've tried every way, and nothing seems to suit them!'

"Nemám nejmenšího ponětí, o čem mluvíte," řekla Alenka.

'I haven't the least idea what you're talking about,' said Alice.

"Zkoušel jsem kořeny stromůa zkoušel jsem břehy a zkoušel jsem křoviny," pokračoval Holub, nevšímaje si její poznámky, "ale ti hadi - nelze se jim zavděčit!

'I've tried the roots of trees, and I've tried banks, and I've tried hedges,' the Pigeon went on, without attending to her; 'but those serpents! There's no pleasing them!'

Alenka byla stále víc a více zmatena, pomyslilasi však, že není nic platno mluviti, dokud Holub neskončí.

Alice was more and more puzzled, but she thought there was no use in saying anything more till the Pigeon had finished.

"Jako kdyby to nedalo dost práce snášet vajíčka," řekl Holub, "ještěabych dnem a nocí byl na stráži proti hadům! A už tři týdny jsem oka nezahmouřil!"

'As if it wasn't trouble enough hatching the eggs,' said the Pigeon; 'but I must be on the look-out for serpents night and day! Why, I haven't had a wink of sleep these three weeks!'

"Je mi velmi líto, že jste byl obtěžován," řekla Alenka, která začínala rozumět smyslu Holubova nářku.

'I'm very sorry you've been annoyed,' said Alice, who was beginning to see its meaning.

"A zrovna když jsem si udělal hnízdo na nejvyšším stroměv celém lese," pokračoval Holub, zvedaje hlas v ostré úpění, "a zrovna když jsem se začal těšit, že od nich budu mít konečně pokoj, musí se připlazit ze samé oblohy! Uf, Hade!"

'And just as I'd taken the highest tree in the wood,' continued the Pigeon, raising its voice to a shriek, 'and just as I was thinking I should be free of them at last, they must needs come wriggling down from the sky! Ugh, Serpent!'

"Ale vždyťvám povídám, že nejsem had," řekla Alenka, "já jsem - já jsem - - "

'But I'm NOT a serpent, I tell you!' said Alice. 'I'm a—I'm a—'

"Co jste?" řekl Holub. "Vidím, že se pokoušíte něco vymyslet !"

'Well! WHAT are you?' said the Pigeon. 'I can see you're trying to invent something!'

"Já - já jsem malé děvčátko," řekla Alenka trochu nejistě, vzpomenuvši si na všechny změny, kterými toho dne prošla.

'I—I'm a little girl,' said Alice, rather doubtfully, as she remembered the number of changes she had gone through that day.

"Velmi chytře vymyšleno!" řekl Holub hlasem, vyjadřujícím nejhlubší pohrdání. "Viděl jsem ve svém životěpěkných pár děvčátek, ale ani jedno s takovýmhle krkem! Ne, ne! Vy jste had, a nic vám to není platno zapírat. Ještěmi budete chtít namluvit,že jste nikdy neokusila vajíčka!"

'A likely story indeed!' said the Pigeon in a tone of the deepest contempt. 'I've seen a good many little girls in my time, but never ONE with such a neck as that! No, no! You're a serpent; and there's no use denying it. I suppose you'll be telling me next that you never tasted an egg!'

"Nu, vajíčka jsem okusila, to jistě," řekla Alenka, která byla dítkem pravdomluvným, "ale děvčátka jedí vajíčka jako hadi, víte ?

'I HAVE tasted eggs, certainly,' said Alice, who was a very truthful child; 'but little girls eat eggs quite as much as serpents do, you know.'

"Tomu nevěřím," řekl Holub; "ale je-li to pravda, pak jsou to také hadi, a to je všechno, co mohu říci."

'I don't believe it,' said the Pigeon; 'but if they do, why then they're a kind of serpent, that's all I can say.'

To byla pro Alenku myšlenka tak nová, že na nějakou chvíli zůstala beze slova, což poskytlo Holubu příležitost, aby dodal: "Hledáte vajíčka, to vím velmi dobře; a co mi na tom záleží, jste-li děvčátko, nebo had?"

This was such a new idea to Alice, that she was quite silent for a minute or two, which gave the Pigeon the opportunity of adding, 'You're looking for eggs, I know THAT well enough; and what does it matter to me whether you're a little girl or a serpent?'

"Mněna tom záleží velmi mnoho," řekla Alenka spěšně, "ale náhodou nehledám vajíčka, a kdybych je hledala, tak nestojím o vaše: nemám je ráda syrová."

'It matters a good deal to ME,' said Alice hastily; 'but I'm not looking for eggs, as it happens; and if I was, I shouldn't want YOURS: I don't like them raw.'

"Tak se odsud kliďte!" řekl Holub nevrle, usedaje zase do svého hnízda. Alenka se shýbala mezi stromy, jak nejlépe mohla, neboťse jí krk stále zaplétal do větví a každou chvíli musela zastavit a vyplést jej. Po chvíli si vzpomněla, že ještědrží v rukou úlomky hřibu, a pozorněse dala do práce, ukusujíc tu z jedné, tu z druhé ruky, chvílemi vyrůstajíc a chvílemi se zmenšujíc, až se jí podařilo najít pravou výšku. Bylo tomu již tak dlouho, co neměla svou pravou míru, že se jí to zprvu zdálo docela podivné; ale v několika minutách si na to opět zvykla a počala k soběmluvit jako obvykle.

'Well, be off, then!' said the Pigeon in a sulky tone, as it settled down again into its nest. Alice crouched down among the trees as well as she could, for her neck kept getting entangled among the branches, and every now and then she had to stop and untwist it. After a while she remembered that she still held the pieces of mushroom in her hands, and she set to work very carefully, nibbling first at one and then at the other, and growing sometimes taller and sometimes shorter, until she had succeeded in bringing herself down to her usual height.

"Nu tak, teďjsem tedy hotova s polovinou svého plánu! Jak podivné jsou všechny tyto změny! Nikdy si nejsem jista, co se se mnou stane v příští chvíli! Nicméněteďjsem se tedy vrátila do své pravé velikosti: teďmi jen zbývá dostat se do té krásné zahrady - jen jak to provést, to bych ráda věděla!" Po těchto slovech vyšla náhle na mýtinu, na které stál malý domek, asi čtyři stopy vysoký. "Aťsi tu bydlí kdo chce," pomyslila si Alenka, "nemohu k němu přijít takhle veliká; vždyťby leknutím ztratil rozum!" Začala tedy opatrněukusovati úlomku, který ještědržela v pravé ruce, a neodvážila sejít poblíž domu, dokud se nezmenšila asi na devět palců.

It was so long since she had been anything near the right size, that it felt quite strange at first; but she got used to it in a few minutes, and began talking to herself, as usual. 'Come, there's half my plan done now! How puzzling all these changes are! I'm never sure what I'm going to be, from one minute to another! However, I've got back to my right size: the next thing is, to get into that beautiful garden—how IS that to be done, I wonder?' As she said this, she came suddenly upon an open place, with a little house in it about four feet high. 'Whoever lives there,' thought Alice, 'it'll never do to come upon them THIS size: why, I should frighten them out of their wits!' So she began nibbling at the righthand bit again, and did not venture to go near the house till she had brought herself down to nine inches high.

Audio from LibreVox.org