Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

CHAPTER VI.

Розділ шостий

Pig and Pepper

Порося та перець

For a minute or two she stood looking at the house, and wondering what to do next, when suddenly a footman in livery came running out of the wood—(she considered him to be a footman because he was in livery: otherwise, judging by his face only, she would have called him a fish)—and rapped loudly at the door with his knuckles. It was opened by another footman in livery, with a round face, and large eyes like a frog; and both footmen, Alice noticed, had powdered hair that curled all over their heads. She felt very curious to know what it was all about, and crept a little way out of the wood to listen.

Хвилину-другу вона дивилася на будиночок, гадаючи, як бути далі. Раптом з лісу вибіг лакей у лівреї і гучно затарабанив у двері кісточками пальців. (Що то лакей, вона здогадалася завдяки лівреї, бо з лиця то був радше карась.) Відчинив йому другий лакей - кругловидий, з лупатими очима, схожий на жабу. Аліса завважила, що обидва мали дрібно закручене й напудрене волосся. Їй страшенно закортіло дізнатися, що ж буде далі, - вона висунулася з гущавини й наставила вуха.

The Fish-Footman began by producing from under his arm a great letter, nearly as large as himself, and this he handed over to the other, saying, in a solemn tone, 'For the Duchess. An invitation from the Queen to play croquet.' The Frog-Footman repeated, in the same solemn tone, only changing the order of the words a little, 'From the Queen. An invitation for the Duchess to play croquet.'

Лакей-Карась видобув з-під пахви величезного - завбільшки, як він сам, листа і, простягши його Жабунові, врочисто оголосив:

- Для Герцогині. Запрошення від Королеви на крокет.

Лакей-Жабун узяв листа і тим самим тоном повторив ті самі слова, ледь змінивши їхній порядок:

- Від Королеви. Запрошення на крокет для Герцогині.

Then they both bowed low, and their curls got entangled together.

Відтак обидва вдарили один одному чолом - так низько, аж посплутувалися кучериками.

Alice laughed so much at this, that she had to run back into the wood for fear of their hearing her; and when she next peeped out the Fish-Footman was gone, and the other was sitting on the ground near the door, staring stupidly up into the sky.

Аліса мусила втекти назад у хащу, щоб не чутно було її сміху. Коли вона визирнула знову, лакея-Карася вже не було, а Жабун сидів біля дверей і тупо зирив у небо.

Alice went timidly up to the door, and knocked.

Аліса несміливо підступила до дверей і постукала.

'There's no sort of use in knocking,' said the Footman, 'and that for two reasons. First, because I'm on the same side of the door as you are; secondly, because they're making such a noise inside, no one could possibly hear you.' And certainly there was a most extraordinary noise going on within—a constant howling and sneezing, and every now and then a great crash, as if a dish or kettle had been broken to pieces.

- З вашого стуку, як з риби пір'я, - зауважив лакей, - і то з двох причин. По-перше, я по той самий бік, що й ви, а по-друге, там такий шарварок, що вас однак не почують.

І справді, гармидер усередині стояв пекельний: хтось верещав, хтось чхав, і час від часу чувся оглушливий брязкіт, наче там били посуд.

'Please, then,' said Alice, 'how am I to get in?'

- Тоді скажіть, будь ласка, - озвалася Аліса, - як мені туди зайти?

'There might be some sense in your knocking,' the Footman went on without attending to her, 'if we had the door between us. For instance, if you were INSIDE, you might knock, and I could let you out, you know.' He was looking up into the sky all the time he was speaking, and this Alice thought decidedly uncivil. 'But perhaps he can't help it,' she said to herself; 'his eyes are so VERY nearly at the top of his head. But at any rate he might answer questions.—How am I to get in?' she repeated, aloud.

- Ваш стук мав би якийсь сенс, - провадив Жабун, не зважаючи на неї, - якби двері були між нами. Приміром, коли б ви постукали з того боку - я б вас, звичайно, випустив.

Кажучи так, він не переставав дивитися в небо. Алісі це здалося жахливою нечемністю. "Хоча, можливо, він і не винен, - сказала вона про себе. - Просто очі в нього майже на маківці. Але принаймні він міг би відповідати на запитання".

- То як мені туди зайти? - голосно повторила Аліса.

'I shall sit here,' the Footman remarked, 'till tomorrow—'

- Я тут сидітиму, - зауважив лакей, - аж до завтрього...

At this moment the door of the house opened, and a large plate came skimming out, straight at the Footman's head: it just grazed his nose, and broke to pieces against one of the trees behind him.

Тут двері розчахнулися, і звідти вилетів великий таріль - він бринів просто лакеєві в голову, але в останню мить тільки черкнув по носі й розбився об дерево в нього за плечима.

'—or next day, maybe,' the Footman continued in the same tone, exactly as if nothing had happened.

- ... а може, й до післязавтрього, - тим самісіньким тоном провадив лакей, мовби нічого й не сталося.

'How am I to get in?' asked Alice again, in a louder tone.

- Як же мені туди зайти? - ще голосніше повторила Аліса.

'ARE you to get in at all?' said the Footman. 'That's the first question, you know.'

- А це ще, знаєте, не вгадано, - сказав лакей, - чи вам взагалі треба туди заходити. Ось головне питання, чи не так?

It was, no doubt: only Alice did not like to be told so. 'It's really dreadful,' she muttered to herself, 'the way all the creatures argue. It's enough to drive one crazy!'

Так, звичайно, - та тільки Аліса не любила, коли з нею розмовляли таким тоном. "Це просто жахливо, - проказала вона сама до себе, - як вони всі тут люблять сперечатися!"

The Footman seemed to think this a good opportunity for repeating his remark, with variations. 'I shall sit here,' he said, 'on and off, for days and days.'

Лакей-Жабун, схоже, вирішив, що саме час повторити своє зауваження на інший лад.

- Я сидітиму тут, - сказав він, - вряди-годи, день у день...

'But what am I to do?' said Alice.

- А що робити мені? - запитала Аліса.

'Anything you like,' said the Footman, and began whistling.

- Що завгодно, - відповів Жабун і засвистав.

'Oh, there's no use in talking to him,' said Alice desperately: 'he's perfectly idiotic!' And she opened the door and went in.

- Ет, що з ним балакати! - розпачливо подумала Аліса. - Він же дурний, аж світиться! - і вона штовхнула двері й переступила поріг.

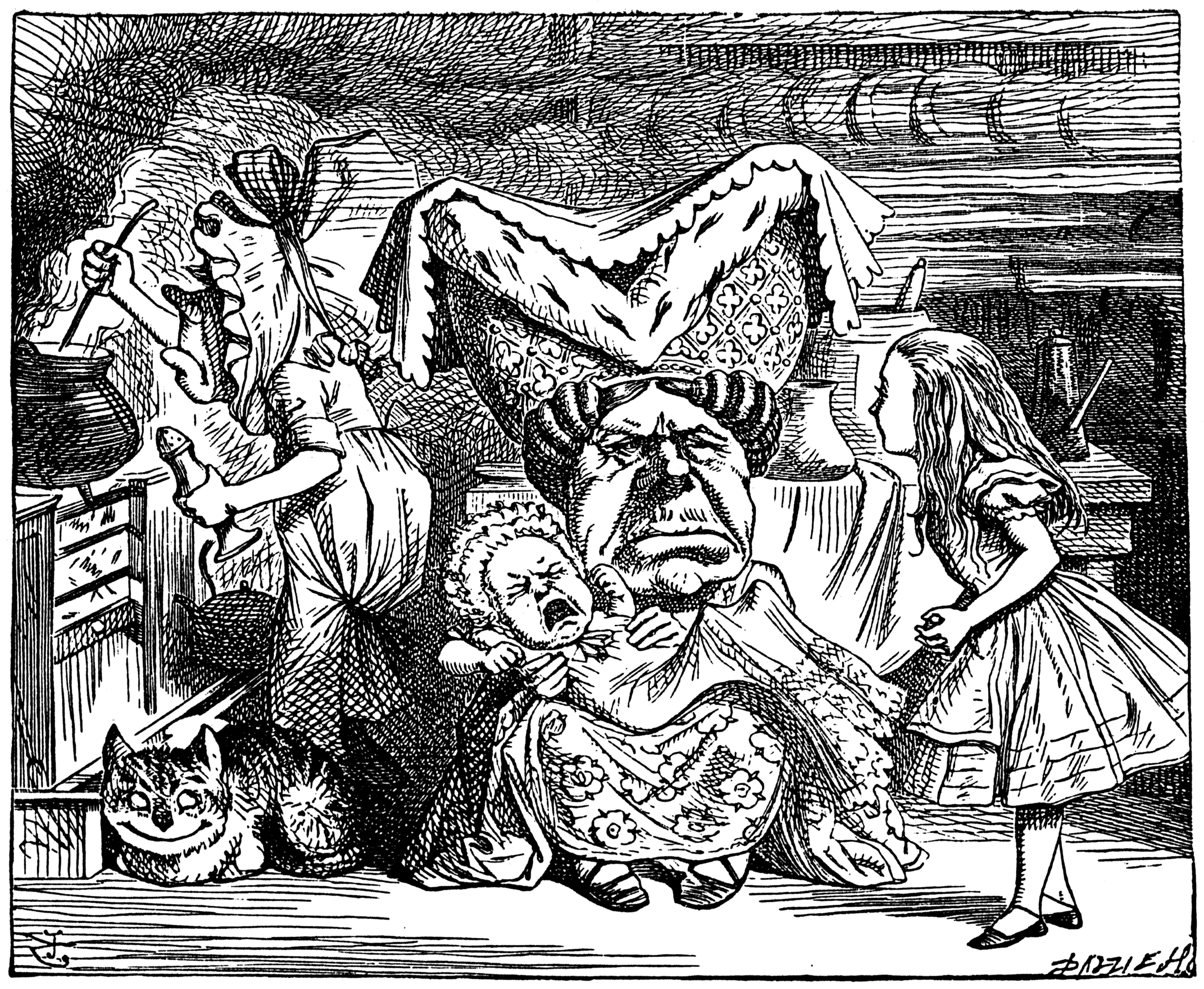

The door led right into a large kitchen, which was full of smoke from one end to the other: the Duchess was sitting on a three-legged stool in the middle, nursing a baby; the cook was leaning over the fire, stirring a large cauldron which seemed to be full of soup.

У просторій кухні дим стояв аж під саму стелю. Посередині на триногому дзиґлику сиділа Герцогиня й чукикала немовля; кухарка схилилася над вогнищем і помішувала щось у величезному казані - з усього видно, юшку.

'There's certainly too much pepper in that soup!' Alice said to herself, as well as she could for sneezing.

- Їхня юшка явно переперчена! - сказала Аліса сама до себе, чхаючи за кожним словом.

There was certainly too much of it in the air. Even the Duchess sneezed occasionally; and as for the baby, it was sneezing and howling alternately without a moment's pause. The only things in the kitchen that did not sneeze, were the cook, and a large cat which was sitting on the hearth and grinning from ear to ear.

Навіть їхнє повітря - і те було переперчене. Чхала навіть Герцогиня; що ж до немовляти, то воно без угаву ревло і чхало, чхало і ревло. Не чхали в кухні лише двоє: кухарка та дебелий, з усмішкою від вуха до вуха, кіт, який сидів на припічку.

'Please would you tell me,' said Alice, a little timidly, for she was not quite sure whether it was good manners for her to speak first, 'why your cat grins like that?'

- Чи не сказали б ви мені ласкаво, - трохи боязко спитала Аліса, бо не була цілком певна, чи годилося їй озиватися першою, - чому ваш кіт такий дурносміх?

'It's a Cheshire cat,' said the Duchess, 'and that's why. Pig!'

- Бо він - чеширський!* - пояснила Герцогиня. - Ох ти ж порося!

She said the last word with such sudden violence that Alice quite jumped; but she saw in another moment that it was addressed to the baby, and not to her, so she took courage, and went on again:—

Останнє слово пролунало так зненацька і з такою нестямною люттю, що Аліса аж підскочила. Проте вона зараз же збагнула, що це стосується не її, а немовляти, і, набравшись духу, повела далі:

'I didn't know that Cheshire cats always grinned; in fact, I didn't know that cats COULD grin.'

- А я й не знала, що чеширські коти вміють сміятися.

'They all can,' said the Duchess; 'and most of 'em do.'

- Коти із графства Чешир сміються на весь шир, - сказала Герцогиня. - Майже всі.

'I don't know of any that do,' Alice said very politely, feeling quite pleased to have got into a conversation.

- Я таких котів ще не бачила, - чемно мовила Аліса, рада-радісінька, що розмова налагодилася.

'You don't know much,' said the Duchess; 'and that's a fact.'

- Ти ще багато чого не бачила, - сказала Герцогиня. - Це зрозуміло.

Alice did not at all like the tone of this remark, and thought it would be as well to introduce some other subject of conversation. While she was trying to fix on one, the cook took the cauldron of soup off the fire, and at once set to work throwing everything within her reach at the Duchess and the baby—the fire-irons came first; then followed a shower of saucepans, plates, and dishes. The Duchess took no notice of them even when they hit her; and the baby was howling so much already, that it was quite impossible to say whether the blows hurt it or not.

Алісі не дуже сподобався тон цього зауваження, і вона подумала, що не завадило б перевести розмову на щось інше. Поки вона підшукувала тему, кухарка зняла з вогню казан і заходилася шпурляти чим попало в Герцогиню та немовля. Першими полетіли кочерга зі щипцями, за ними градом посипалися блюдця, тарілки й полумиски, та Герцогиня і бровою не повела, хоч дещо в неї й поцілило; а немовля й доти ревма ревло, тож зрозуміти, болить йому від ударів чи ні, було неможливо.

'Oh, PLEASE mind what you're doing!' cried Alice, jumping up and down in an agony of terror. 'Oh, there goes his PRECIOUS nose'; as an unusually large saucepan flew close by it, and very nearly carried it off.

- Ой, що ви робите? Схаменіться! Благаю! - кричала Аліса, підстрибуючи зі страху. - Ой, просто в ніс! Бідний носик!

У цю мить страхітливих розмірів баняк прохурчав так близько від немовляти, що ледь не відбив йому носа.

'If everybody minded their own business,' the Duchess said in a hoarse growl, 'the world would go round a deal faster than it does.'

- Якби ніхто не пхав свого носа до чужого проса, - хрипким басом сказала Герцогиня, - земля крутилася б куди шпаркіше.

'Which would NOT be an advantage,' said Alice, who felt very glad to get an opportunity of showing off a little of her knowledge. 'Just think of what work it would make with the day and night! You see the earth takes twenty-four hours to turn round on its axis—'

- Ну й що б це дало? - зауважила Аліса, рада похизуватися своїми знаннями. - Подумайте лишень, що сталося б із днем і ніччю. Земля оберталася б навколо осі швидше, ніж...

'Talking of axes,' said the Duchess, 'chop off her head!'

- До речі, про ніж! - сказала Герцогиня. - Відтяти їй голову!

Alice glanced rather anxiously at the cook, to see if she meant to take the hint; but the cook was busily stirring the soup, and seemed not to be listening, so she went on again: 'Twenty-four hours, I THINK; or is it twelve? I—'

Аліса тривожно глипнула на кухарку, але та пустила ці слова повз вуха і знай собі помішувала юшку. Тож Аліса докінчила:

- ...ніж раз на добу, себто раз на двадцять чотири години... чи, може, на дванадцять?..

'Oh, don't bother ME,' said the Duchess; 'I never could abide figures!' And with that she began nursing her child again, singing a sort of lullaby to it as she did so, and giving it a violent shake at the end of every line:

- О, дай мені спокій! - урвала її Герцогиня. - Зроду не терпіла арифметики!

Вона завела щось наче колискову і заходилася чукикати немовля, люто стрясаючи його наприкінці кожного рядка.

'Speak roughly to your little boy,

And beat him when he sneezes:

He only does it to annoy,

Because he knows it teases.'

Бурчи, кричи на немовля*,

Лупи його, як чхає,

Що те чхання нам дошкуля,

Маля прекрасно знає...

CHORUS.

(In which the cook and the baby joined):—

'Wow! wow! wow!'

Хор

(З участю кухарки та маляти):

Гу! Гу! Гу!

While the Duchess sang the second verse of the song, she kept tossing the baby violently up and down, and the poor little thing howled so, that Alice could hardly hear the words:—

Співаючи другу строфу, Герцогиня не переставала несамовито трясти немовля, а воно, сердешне, так репетувало, що Алісі нелегко було розібрати слова:

'I speak severely to my boy,

I beat him when he sneezes;

For he can thoroughly enjoy

The pepper when he pleases!'

Бурчу, кричу на немовля,

Луплю його, як чхає.

Нехай маля не дошкуля -

До перчику звикає!

CHORUS.

'Wow! wow! wow!'

Хор:

Гу!Гу!Гу!

'Here! you may nurse it a bit, if you like!' the Duchess said to Alice, flinging the baby at her as she spoke. 'I must go and get ready to play croquet with the Queen,' and she hurried out of the room. The cook threw a frying-pan after her as she went out, but it just missed her.

- Тримай! - крикнула раптом Герцогиня до Аліси і швиргонула в неї немовлям. - Можеш трохи поняньчити, як маєш охоту! Мені пора збиратися до Королеви на крокет!

І вона хутко вийшла. Кухарка жбурнула їй навздогін сковороду, але, на диво, схибила.

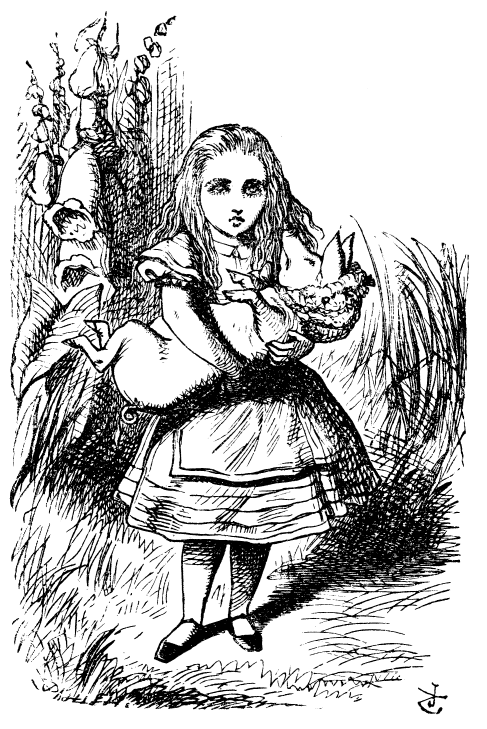

Alice caught the baby with some difficulty, as it was a queer-shaped little creature, and held out its arms and legs in all directions, 'just like a star-fish,' thought Alice. The poor little thing was snorting like a steam-engine when she caught it, and kept doubling itself up and straightening itself out again, so that altogether, for the first minute or two, it was as much as she could do to hold it.

Спіймати дитину виявилося не так просто: руки й ноги в того чудернацького створіннячка були розчепірені на всі боки ("Достоту, як у морської зірки", - подумала Аліса), а само воно пихтіло, як паровик, і без упину пручалося.

As soon as she had made out the proper way of nursing it, (which was to twist it up into a sort of knot, and then keep tight hold of its right ear and left foot, so as to prevent its undoing itself,) she carried it out into the open air. 'IF I don't take this child away with me,' thought Alice, 'they're sure to kill it in a day or two: wouldn't it be murder to leave it behind?' She said the last words out loud, and the little thing grunted in reply (it had left off sneezing by this time). 'Don't grunt,' said Alice; 'that's not at all a proper way of expressing yourself.'

Нарешті вона знайшла належний спосіб укоськати немовля: скрутила його у вузол, міцно схопила за праве вушко та ліву ніжку (щоб не розкрутилося), і вийшла з ним на свіже повітря.

- Якщо його звідси не забрати, - подумала Аліса, - то вони напевне його приб'ють, - як не нині, то завтра. Було б злочинно його покинути, правда ж?

Останні слова вона проказала вголос, і маля рохнуло їй у відповідь (чхати воно вже перестало)^.

- Не рохкай, - сказала Аліса. - Висловлюй свої почуття у якийсь інший спосіб!

The baby grunted again, and Alice looked very anxiously into its face to see what was the matter with it. There could be no doubt that it had a VERY turn-up nose, much more like a snout than a real nose; also its eyes were getting extremely small for a baby: altogether Alice did not like the look of the thing at all. 'But perhaps it was only sobbing,' she thought, and looked into its eyes again, to see if there were any tears.

Та немовля рохнуло знову, й Аліса прискіпливо зазирнула йому в личко, аби з'ясувати причину. Ніс у нього був, без сумніву, аж надміру кирпатий, більше схожий на рильце, ніж на справжнього носа, та й очі зробилися підозріло маленькі як на дитину. Словом, його вигляд Алісі не сподобався. "А може, то воно так схлипує?" - подумала вона і зазирнула маляті в очі, чи не видно там сліз.

No, there were no tears. 'If you're going to turn into a pig, my dear,' said Alice, seriously, 'I'll have nothing more to do with you. Mind now!' The poor little thing sobbed again (or grunted, it was impossible to say which), and they went on for some while in silence.

Ба ні, жодної сльозинки!..

- Якщо ти, золотко, збираєшся перекинутися поросям, - поважно мовила Аліса, - я не буду з тобою панькатися. Закарбуй це собі на носі!

Немовля знову схлипнуло (а чи зрохнуло - важко було сказати), й Аліса якийсь час несла його мовчки.

Alice was just beginning to think to herself, 'Now, what am I to do with this creature when I get it home?' when it grunted again, so violently, that she looked down into its face in some alarm. This time there could be NO mistake about it: it was neither more nor less than a pig, and she felt that it would be quite absurd for her to carry it further.

Вона вже починала хвилюватися - ото буде клопіт із цим чудом удома! - коли це раптом воно знову рохнуло, та так виразно, що Аліса не без тривоги ще раз глянула йому в обличчя. Так, цього разу помилитися було годі: перед нею було найсправжнісіньке порося! Носитися з ним далі було безглуздо.

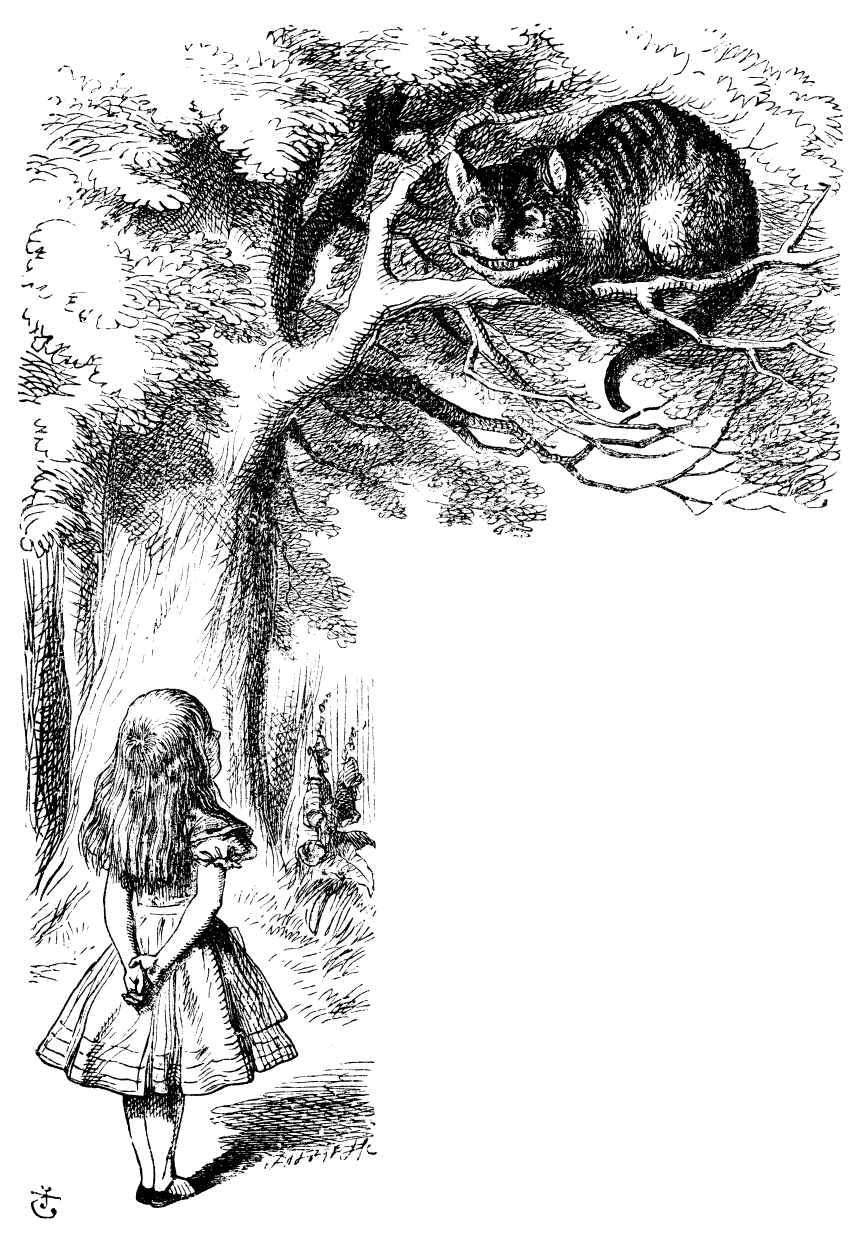

So she set the little creature down, and felt quite relieved to see it trot away quietly into the wood. 'If it had grown up,' she said to herself, 'it would have made a dreadfully ugly child: but it makes rather a handsome pig, I think.' And she began thinking over other children she knew, who might do very well as pigs, and was just saying to herself, 'if one only knew the right way to change them—' when she was a little startled by seeing the Cheshire Cat sitting on a bough of a tree a few yards off.

Вона опустила порося на землю і вельми втішилась, коли воно спокійнісінько потрюхикало собі в хащу.

- З нього виросла б страх яка бридка дитина, - подумала Аліса. - А як порося, по-моєму, воно досить симпатичне.

І вона стала пригадувати деяких знайомих їй дітей, з яких могли б вийти незгірші поросята ("Аби лиш знаття, як міняти їхню подобу", - подумала вона), і раптом здригнулася з несподіванки: за кілька кроків від неї на гілляці сидів Чеширський Кіт.

The Cat only grinned when it saw Alice. It looked good-natured, she thought: still it had VERY long claws and a great many teeth, so she felt that it ought to be treated with respect.

Кіт натомість лише усміхнувся.

"На вигляд наче добродушний, - подумала Аліса, - але які в нього пазурі та зуби!.. Варто з ним триматися шанобливо".

'Cheshire Puss,' she began, rather timidly, as she did not at all know whether it would like the name: however, it only grinned a little wider. 'Come, it's pleased so far,' thought Alice, and she went on. 'Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?'

- Мурчику-Чеширчику, - непевно почала вона, не знаючи, чи сподобається йому таке звертання.

Кіт, однак, знову всміхнувся, тільки трохи ширше. "Ніби сподобалося," - подумала Аліса, й повела далі:

- Чи не були б ви такі ласкаві сказати, як мені звідси вибратися?

'That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,' said the Cat.

- Залежить, куди йти, - відказав Кіт.

'I don't much care where—' said Alice.

- Власне, мені однаково, куди йти... - почала Аліса.

'Then it doesn't matter which way you go,' said the Cat.

- Тоді й однаково, яким шляхом, - зауважив Кіт.

'—so long as I get SOMEWHERE,' Alice added as an explanation.

-... аби лиш кудись дійти, - докінчила Аліса.

'Oh, you're sure to do that,' said the Cat, 'if you only walk long enough.'

- О, кудись та дійдеш, - сказав Кіт. - Треба тільки достатньо пройти.

Alice felt that this could not be denied, so she tried another question. 'What sort of people live about here?'

Цьому годі було заперечити, тож Аліса спитала дещо інше:

- А які тут люди проживають?

'In THAT direction,' the Cat said, waving its right paw round, 'lives a Hatter: and in THAT direction,' waving the other paw, 'lives a March Hare. Visit either you like: they're both mad.'

- Он там, - Кіт махнув правою лапою, - живе Капелюшник, - а отам (він махнув лівою) - Шалений Заєць. - Завітай до кого хочеш: у них обох не всі вдома*.

'But I don't want to go among mad people,' Alice remarked.

- Але я з такими не товаришую, - зауважила Аліса.

'Oh, you can't help that,' said the Cat: 'we're all mad here. I'm mad. You're mad.'

- Іншої ради нема, - сказав Кіт. - У нас у всіх не всі вдома. У мене не всі вдома. У тебе не всі вдома.

'How do you know I'm mad?' said Alice.

- Хто сказав, що у мене не всі вдома? - запитала Аліса.

'You must be,' said the Cat, 'or you wouldn't have come here.'

- Якщо у тебе всі вдома, - сказав Кіт, - то чого ти тут?

Alice didn't think that proved it at all; however, she went on 'And how do you know that you're mad?'

Аліса вважала, що це ще ніякий не доказ, проте не стала сперечатися, а лише спитала:

- А хто сказав, що у вас не всі вдома?

'To begin with,' said the Cat, 'a dog's not mad. You grant that?'

- Почнімо з собаки, - мовив Кіт. - Як гадаєш, у собаки всі вдома?

'I suppose so,' said Alice.

- Мабуть, так, - сказала Аліса.

'Well, then,' the Cat went on, 'you see, a dog growls when it's angry, and wags its tail when it's pleased. Now I growl when I'm pleased, and wag my tail when I'm angry. Therefore I'm mad.'

- А тепер - дивися, - вів далі Кіт. - Собака спересердя гарчить, а з утіхи меле хвостом. А я мелю хвостом - спересердя, а від радощів гарчу. Отже, у мене не всі вдома.

'I call it purring, not growling,' said Alice.

- Я називаю це мурчанням, а не гарчанням, - зауважила Аліса.

'Call it what you like,' said the Cat. 'Do you play croquet with the Queen to-day?'

- Називай як хочеш, - відказав Кіт. - Чи граєш ти сьогодні в крокет у Королеви?

'I should like it very much,' said Alice, 'but I haven't been invited yet.'

- Я б залюбки, - відповіла Аліса, - тільки мене ще не запрошено.

'You'll see me there,' said the Cat, and vanished.

- Побачимося там, - кинув Кіт і щез із очей.

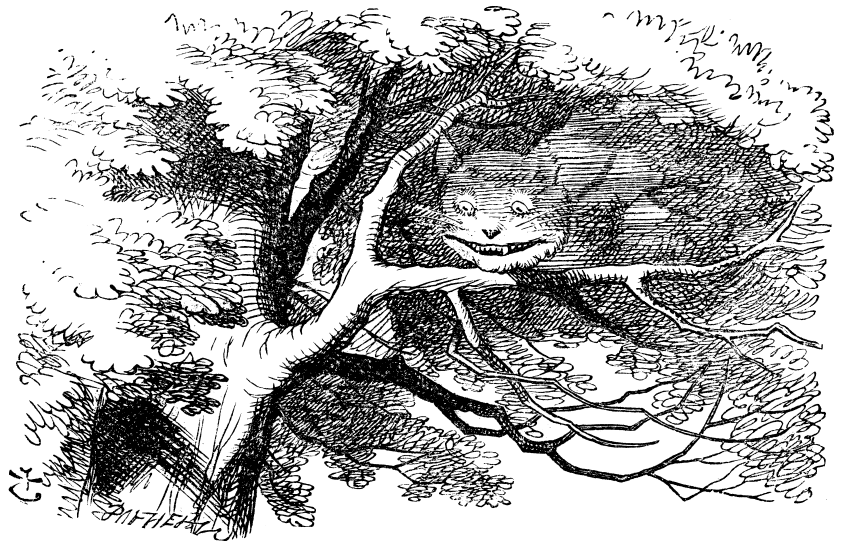

Alice was not much surprised at this, she was getting so used to queer things happening. While she was looking at the place where it had been, it suddenly appeared again.

Аліса не дуже й здивувалася: вона вже почала звикати до всяких чудес. Вона стояла й дивилася на ту гілку, де щойно сидів Кіт, коли це раптом він вигулькнув знову.

'By-the-bye, what became of the baby?' said the Cat. 'I'd nearly forgotten to ask.'

- Між іншим, що сталося з немовлям? - поцікавився Кіт. - Ледь не забув спитати.

'It turned into a pig,' Alice quietly said, just as if it had come back in a natural way.

- Воно перекинулося в порося, - не змигнувши оком, відповіла Аліса.

'I thought it would,' said the Cat, and vanished again.

- Я так і думав, - сказав Кіт і знову щез.

Alice waited a little, half expecting to see it again, but it did not appear, and after a minute or two she walked on in the direction in which the March Hare was said to live. 'I've seen hatters before,' she said to herself; 'the March Hare will be much the most interesting, and perhaps as this is May it won't be raving mad—at least not so mad as it was in March.' As she said this, she looked up, and there was the Cat again, sitting on a branch of a tree.

Аліса трохи почекала - ану ж він з'явиться ще раз, - а тоді подалася в той бік, де, як було їй сказано, мешкав Шалений Заєць.

- Капелюшників я вже бачила, - мовила вона подумки, - а от Шалений Заєць - це значно цікавіше. Можливо, тепер, у травні, він буде не такий шалено лютий, як, скажімо, у лютому...

Тут вона звела очі й знову побачила Кота.

'Did you say pig, or fig?' said the Cat.

- Як ти сказала? - спитав Кіт. - У порося чи в карася?

'I said pig,' replied Alice; 'and I wish you wouldn't keep appearing and vanishing so suddenly: you make one quite giddy.'

- Я сказала "в порося", - відповіла Аліса. - І чи могли б ви надалі з'являтися й зникати не так швидко: від цього йде обертом голова.

'All right,' said the Cat; and this time it vanished quite slowly, beginning with the end of the tail, and ending with the grin, which remained some time after the rest of it had gone.

- Гаразд, - сказав Кіт, і став зникати шматками: спочатку пропав кінчик його хвоста, а насамкінець - усміх, що ще якийсь час висів у повітрі.

'Well! I've often seen a cat without a grin,' thought Alice; 'but a grin without a cat! It's the most curious thing I ever saw in my life!'

- Гай-гай! - подумала Аліса. - Котів без усмішки я, звичайно, зустрічала, але усмішку без кота!.. Це найбільша дивовижа в моєму житті!

She had not gone much farther before she came in sight of the house of the March Hare: she thought it must be the right house, because the chimneys were shaped like ears and the roof was thatched with fur. It was so large a house, that she did not like to go nearer till she had nibbled some more of the lefthand bit of mushroom, and raised herself to about two feet high: even then she walked up towards it rather timidly, saying to herself 'Suppose it should be raving mad after all! I almost wish I'd gone to see the Hatter instead!'

До Шаленого Зайця довго йти не довелося: садиба, яку вона невдовзі побачила, належала, безперечно, йому, бо два димарі на даху виглядали, як заячі вуха, а дах був накритий хутром. Сама садиба виявилася такою великою, що Аліса не квапилася підходити ближче, поки не відкусила чималий кусник гриба в лівій руці й довела свій зріст до двох футів. Але й тепер вона рушила з осторогою. "А що, як він і досі буйний?" - думала вона. - Краще б я загостила до Капелюшника!"

Audio from LibreVox.org