Приключения Алисы в стране чудес

Глава V.

CHAPTER V.

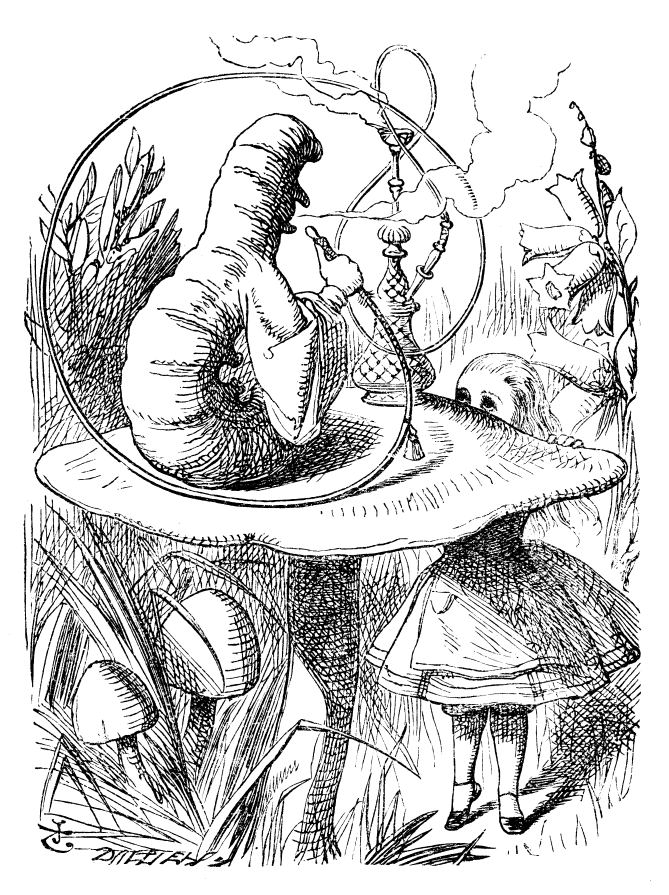

СИНЯЯ ГУСЕНИЦА ДАЕТ СОВЕТ

Advice from a Caterpillar

Алиса и Синяя Гусеница долго смотрели друг на друга, не говоря ни слова. Наконец, Гусеница вынула кальян изо рта и медленно, словно в полусне, заговорила:

The Caterpillar and Alice looked at each other for some time in silence: at last the Caterpillar took the hookah out of its mouth, and addressed her in a languid, sleepy voice.

-- Ты... кто... такая?--спросила Синяя Гусеница.

'Who are YOU?' said the Caterpillar.

Начало не очень-то располагало к беседе. -- Сейчас, право, не знаю, сударыня, -- отвечала Алиса робко. -- Я знаю, кем я была сегодня утром, когда проснулась, но с тех пор я уже несколько раз менялась.

This was not an encouraging opening for a conversation. Alice replied, rather shyly, 'I — I hardly know, sir, just at present—at least I know who I WAS when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.'

-- Что это ты выдумываешь? -- строго спросила Гусеница. -- Да ты в своем уме?

'What do you mean by that?' said the Caterpillar sternly. 'Explain yourself!'

-- Нe знаю,--отвечала Алиса.--Должно быть, в чужом. Видите ли...

'I can't explain MYSELF, I'm afraid, sir' said Alice, 'because I'm not myself, you see.'

-- Не вижу, -- сказала Гусеница.

'I don't see,' said the Caterpillar.

-- Боюсь, что не сумею вам все это объяснить, -- учтиво промолвила Алиса. -- Я и сама ничего не понимаю. Столько превращений в один день хоть кого собьет с толку.

'I'm afraid I can't put it more clearly,' Alice replied very politely, 'for I can't understand it myself to begin with; and being so many different sizes in a day is very confusing.'

-- Не собьет, -- сказала Гусеница.

'It isn't,' said the Caterpillar.

-- Вы с этим, верно еще не сталкивались, -- пояснила Алиса. -- Но когда вам придется превращаться в куколку, а потом в бабочку, вам это тоже покажется странным.

'Well, perhaps you haven't found it so yet,' said Alice; 'but when you have to turn into a chrysalis—you will some day, you know—and then after that into a butterfly, I should think you'll feel it a little queer, won't you?'

-- Нисколько! -- сказала Гусеница.

'Not a bit,' said the Caterpillar.

-- Что ж, возможно,--проговорила Алиса.--Я только знаю, что мне бы это было странно.

'Well, perhaps your feelings may be different,' said Alice; 'all I know is, it would feel very queer to ME.'

-- Тебе! -- повторила Гусеница с презрением. -- А кто ты такая?

'You!' said the Caterpillar contemptuously. 'Who are YOU?'

Это вернуло их к началу беседы. Алиса немного рассердилась -- уж очень неприветливо говорила с ней Гусеница. Она выпрямилась и произнесла, стараясь, чтобы голос ее звучал повнушительнее: -- По-моему, это вы дол жны мне сказать сначала, кто вы такая.

Which brought them back again to the beginning of the conversation. Alice felt a little irritated at the Caterpillar's making such VERY short remarks, and she drew herself up and said, very gravely, 'I think, you ought to tell me who YOU are, first.'

-- Почему? -- спросила Гусеница.

'Why?' said the Caterpillar.

Вопрос поставил Алису в туник. Она ничего не могла придумать, а Гусеница, видно, просто была весьма не в духе, так что Алиса повернулась и пошла прочь.

Here was another puzzling question; and as Alice could not think of any good reason, and as the Caterpillar seemed to be in a VERY unpleasant state of mind, she turned away.

-- Вернись! -- закричала Гусеница ей вслед. -- Мне нужно сказать тебе что-то очень важное.

'Come back!' the Caterpillar called after her. 'I've something important to say!'

Это звучало заманчиво--Алиса вернулась.

This sounded promising, certainly: Alice turned and came back again.

-- Держи себя в руках! -- сказала Гусеница.

'Keep your temper,' said the Caterpillar.

-- Это все? -- спросила Алиса, стараясь не сердиться.

'Is that all?' said Alice, swallowing down her anger as well as she could.

-- Нет,--отвечала Гусеница.

'No,' said the Caterpillar.

Алиса решила подождать--все равно делать ей было нечего, а вдруг все же Гусеница скажет ей что-нибудь стоящее? Сначала та долго сосала кальян, но, наконец, вынула его изо рта и сказала: -- Значит, по-твоему, ты изменилась?

Alice thought she might as well wait, as she had nothing else to do, and perhaps after all it might tell her something worth hearing. For some minutes it puffed away without speaking, but at last it unfolded its arms, took the hookah out of its mouth again, and said, 'So you think you're changed, do you?'

-- Да, сударыня, -- отвечала Алиса, -- и это очень грустно. Все время меняюсь и ничего не помню.

'I'm afraid I am, sir,' said Alice; 'I can't remember things as I used—and I don't keep the same size for ten minutes together!'

-- Чего не помнишь? -- спросила Гусеница.

'Can't remember WHAT things?' said the Caterpillar.

-- Я пробовала прочитать ``Как дорожит любым деньком...'', а получилось что-то совсем другое, -- сказала с тоской Алиса.

'Well, I've tried to say "HOW DOTH THE LITTLE BUSY BEE," but it all came different!' Alice replied in a very melancholy voice.

-- Читай ``Папа Вильям'', -- предложила Гусеница.

'Repeat, "YOU ARE OLD, FATHER WILLIAM,"' said the Caterpillar.

Алиса сложила руки и начала:

Alice folded her hands, and began:—

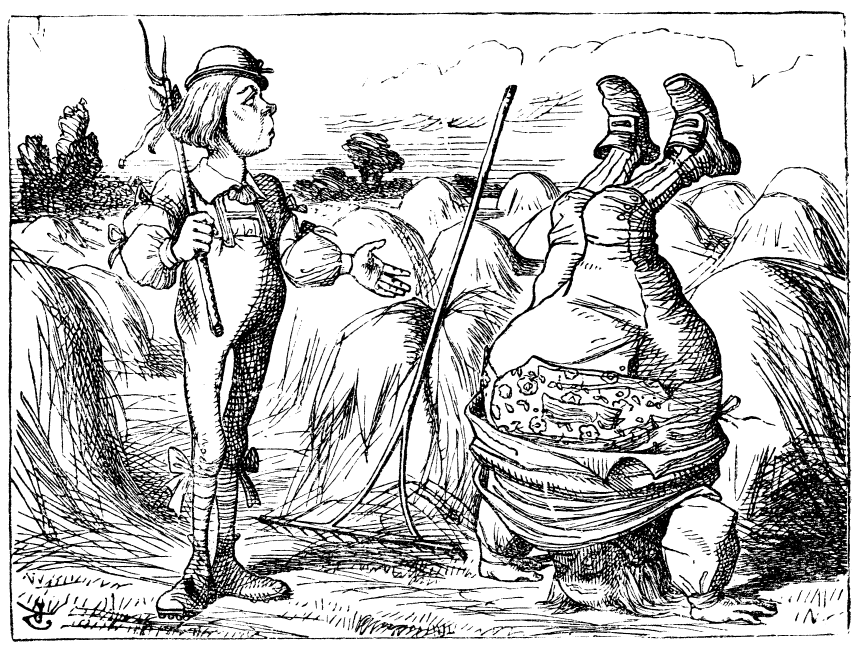

-- Папа Вильям, --сказал любопытный малыш, --

Голова твоя белого цвета.

Между тем ты всегда вверх ногами стоишь.

Как ты думаешь, правильно это?

'You are old, Father William,' the young man said,

'And your hair has become very white;

And yet you incessantly stand on your head—

Do you think, at your age, it is right?'

-- В ранней юности, -- старец промолвил в ответ, --

Я боялся раскинуть мозгами,

Но, узнав, что мозгов в голове моей нет,

Я спокойно стою вверх ногами.

'In my youth,' Father William replied to his son,

'I feared it might injure the brain;

But, now that I'm perfectly sure I have none,

Why, I do it again and again.'

-- Ты старик, -- продолжал любопытный юнец, --

Этот факт я отметил вначале.

Почему ж ты так ловко проделал, отец,

Троекратное сальто-мортале?

'You are old,' said the youth, 'as I mentioned before,

And have grown most uncommonly fat;

Yet you turned a back-somersault in at the door—

Pray, what is the reason of that?'

-- В ранней юности, -- сыну ответил старик, --

Натирался я мазью особой,

На два шиллинга банка -- один золотник,

Вот, не купишь ли банку на пробу?

'In my youth,' said the sage, as he shook his grey locks,

'I kept all my limbs very supple

By the use of this ointment—one shilling the box—

Allow me to sell you a couple?'

-- Ты немолод, -- сказал любознательный сын, --

Сотню лет ты без малого прожил.

Между тем двух гусей за обедом один

Ты от клюва до лап уничтожил.

'You are old,' said the youth, 'and your jaws are too weak

For anything tougher than suet;

Yet you finished the goose, with the bones and the beak—

Pray how did you manage to do it?'

-- В ранней юности мышцы своих челюстей

Я развил изучением права,

И так часто я спорил с женою своей,

Что жевать научился на славу!

'In my youth,' said his father, 'I took to the law,

And argued each case with my wife;

And the muscular strength, which it gave to my jaw,

Has lasted the rest of my life.'

-- Мой отец, ты простишь ли меня, несмотря

На неловкость такого вопроса:

Как сумел удержать ты живого угря

В равновесье на кончике носа?

'You are old,' said the youth, 'one would hardly suppose

That your eye was as steady as ever;

Yet you balanced an eel on the end of your nose—

What made you so awfully clever?'

-- Нет, довольно! -- сказал возмущенный отец. --

Есть границы любому терпенью.

Если пятый вопрос ты задашь, наконец,

Сосчитаешь ступень за ступенью!

'I have answered three questions, and that is enough,'

Said his father; 'don't give yourself airs!

Do you think I can listen all day to such stuff?

Be off, or I'll kick you down stairs!'

-- Все неверно, -- сказала Гусеница.

'That is not said right,' said the Caterpillar.

-- Да, не совсем верно, -- робко согласилась Алиса. -- Некоторые слова не те.

'Not QUITE right, I'm afraid,' said Alice, timidly; 'some of the words have got altered.'

-- Все не так, от самого начала и до самого конца, -- строго проговорила Гусеница. Наступило молчание.

'It is wrong from beginning to end,' said the Caterpillar decidedly, and there was silence for some minutes.

The Caterpillar was the first to speak.

-- А какого роста ты хочешь быть? -- спросила, наконец, Гусеница.

'What size do you want to be?' it asked.

-- Ах, все равно, -- быстро сказала Алиса. -- Только, знаете, так неприятно все время меняться...

'Oh, I'm not particular as to size,' Alice hastily replied; 'only one doesn't like changing so often, you know.'

-- Не знаю, -- отрезала Гусеница.

'I DON'T know,' said the Caterpillar.

Алиса молчала: никогда в жизни ей столько не перечили, и она чувствовала, что теряет терпение.

Alice said nothing: she had never been so much contradicted in her life before, and she felt that she was losing her temper.

-- А теперь ты довольна? -- спросила Гусеница.

'Are you content now?' said the Caterpillar.

-- Если вы не возражаете, сударыня, -- отвечала Алиса, -- мне бы хотелось хоть капельку подрасти. Три дюйма -- такой ужасный рост!

'Well, I should like to be a LITTLE larger, sir, if you wouldn't mind,' said Alice: 'three inches is such a wretched height to be.'

-- Это прекрасный рост! -- сердито закричала Гусеница и вытянулась во всю длину. (В ней было ровно три дюйма).

'It is a very good height indeed!' said the Caterpillar angrily, rearing itself upright as it spoke (it was exactly three inches high).

-- Но я к нему не привыкла! -- жалобно протянула бедная Алиса. А про себя подумала: ``До чего они тут все обидчивые!''

'But I'm not used to it!' pleaded poor Alice in a piteous tone. And she thought of herself, 'I wish the creatures wouldn't be so easily offended!'

-- Со временем привыкнешь, -- возразила Гусеница, сунула кальян в рот и выпустила дым в воздух.

'You'll get used to it in time,' said the Caterpillar; and it put the hookah into its mouth and began smoking again.

Алиса терпеливо ждала, пока Гусеница не соблаговолит снова обратить на нее внимание. Минуты через две та вынула кальян изо рта, зевнула -- раз, другой -- и потянулась. Потом она сползла с гриба и скрылась в траве, бросив Алисе на прощанье: -- Откусишь с одной стороны -- подрастешь, с другой -- уменьшишься!

This time Alice waited patiently until it chose to speak again. In a minute or two the Caterpillar took the hookah out of its mouth and yawned once or twice, and shook itself. Then it got down off the mushroom, and crawled away in the grass, merely remarking as it went, 'One side will make you grow taller, and the other side will make you grow shorter.'

-- С одной стороны чего? -- подумала Алиса. -- С другой стороны чего?

'One side of WHAT? The other side of WHAT?' thought Alice to herself.

-- Гриба, -- ответила Гусеница, словно услышав вопрос, и исчезла из виду.

'Of the mushroom,' said the Caterpillar, just as if she had asked it aloud; and in another moment it was out of sight.

С минуту Алиса задумчиво смотрела на гриб, пытаясь определить, где у него одна сторона, а где--другая; гриб был круглый, и это совсем сбило ее с толку. Наконец, она решилась: обхватила гриб руками и отломила с каждой стороны по кусочку.

Alice remained looking thoughtfully at the mushroom for a minute, trying to make out which were the two sides of it; and as it was perfectly round, she found this a very difficult question. However, at last she stretched her arms round it as far as they would go, and broke off a bit of the edge with each hand.

-- Интересно, какой из них какой?--подумала она и откусила немножко от того, который держала в правой руке. В ту же минуту она почувствовала сильный удар снизу в подбородок: он стукнулся о ноги!

'And now which is which?' she said to herself, and nibbled a little of the right-hand bit to try the effect: the next moment she felt a violent blow underneath her chin: it had struck her foot!

Столь внезапная перемена очень ее напугала; нельзя было терять ни минуты, ибо она стремительно уменьшалась. Алиса взялась за другой кусок, но подбородок ее так прочно прижало к ногам, что она никак не могла открыть рот. Наконец, ей это удалось -- и она откусила немного гриба из левой руки.

She was a good deal frightened by this very sudden change, but she felt that there was no time to be lost, as she was shrinking rapidly; so she set to work at once to eat some of the other bit. Her chin was pressed so closely against her foot, that there was hardly room to open her mouth; but she did it at last, and managed to swallow a morsel of the lefthand bit.

-- Ну вот, голова, наконец, освободилась! -- радостно воскликнула Алиса. Впрочем, радость ее тут же сменилась тревогой: куда-то пропали плечи. Она взглянула вниз, но увидела только шею невероятной длины, которая возвышалась, словно огромный шест, над зеленым морем листвы.

'Come, my head's free at last!' said Alice in a tone of delight, which changed into alarm in another moment, when she found that her shoulders were nowhere to be found: all she could see, when she looked down, was an immense length of neck, which seemed to rise like a stalk out of a sea of green leaves that lay far below her.

-- Что это за зелень? -- промолвила Алиса. -- И куда девались мои плечи? Бедные мои ручки, где вы? Почему я вас не вижу? С этими словами она пошевелила руками, но увидеть их все равно не смогла, только но листве далеко внизу прошел шелест.

'What CAN all that green stuff be?' said Alice. 'And where HAVE my shoulders got to? And oh, my poor hands, how is it I can't see you?' She was moving them about as she spoke, but no result seemed to follow, except a little shaking among the distant green leaves.

Убедившись, что поднять руки к голове не удастся, Алиса решила нагнуть к ним голову и с восторгом убедилась, что шея у нее, словно змея, гнется в любом направлении. Алиса выгнула шею изящным зигзагом, готовясь нырнуть в листву (ей уже стало ясно, что это верхушки деревьев, под которыми она только что стояла), как вдруг послышалось громкое шипение. Она вздрогнула и отступила. Прямо в лицо ей, яростно бия крыльями, кинулась горлица.

As there seemed to be no chance of getting her hands up to her head, she tried to get her head down to them, and was delighted to find that her neck would bend about easily in any direction, like a serpent. She had just succeeded in curving it down into a graceful zigzag, and was going to dive in among the leaves, which she found to be nothing but the tops of the trees under which she had been wandering, when a sharp hiss made her draw back in a hurry: a large pigeon had flown into her face, and was beating her violently with its wings.

-- Змея! -- кричала Горлица.

'Serpent!' screamed the Pigeon.

-- Никакая я не змея!--возмутилась Алиса.--Оставьте меня в покое!

'I'm NOT a serpent!' said Alice indignantly. 'Let me alone!'

-- А я говорю, змея! -- повторила Горлица несколько сдержаннее. И, всхлипнув, прибавила: -- Я все испробовала -- и все без толку. Они не довольны ничем!

'Serpent, I say again!' repeated the Pigeon, but in a more subdued tone, and added with a kind of sob, 'I've tried every way, and nothing seems to suit them!'

-- Понятия не имею, о чем вы говорите! -- сказала Алиса.

'I haven't the least idea what you're talking about,' said Alice.

-- Корни деревьев, речные берега, кусты, -- продолжала Горлица, не слушая. -- Ох, эти змеи! На них не угодишь!

'I've tried the roots of trees, and I've tried banks, and I've tried hedges,' the Pigeon went on, without attending to her; 'but those serpents! There's no pleasing them!'

Алиса недоумевала все больше и больше. Впрочем, она понимала, что, пока Горлица не кончит, задавать ей вопросы бессмысленно.

Alice was more and more puzzled, but she thought there was no use in saying anything more till the Pigeon had finished.

-- Мало того, что я высиживаю птенцов, еще сторожи их день и ночь от змей! Вот уже три недели, как я глаз не сомкнула ни на минутку!

'As if it wasn't trouble enough hatching the eggs,' said the Pigeon; 'but I must be on the look-out for serpents night and day! Why, I haven't had a wink of sleep these three weeks!'

-- Мне очень жаль, что вас так тревожат, -- сказала Алиса. Она начала понимать, в чем дело.

'I'm very sorry you've been annoyed,' said Alice, who was beginning to see its meaning.

-- И стоило мне устроиться на самом высоком дереве, -- продолжала Горлица все громче и громче и наконец срываясь на крик,--стоило мне подумать, что я наконец-то от них избавилась, как нет! Они тут как тут! Лезут на меня прямо с неба! У-у! Змея подколодная!

'And just as I'd taken the highest tree in the wood,' continued the Pigeon, raising its voice to a shriek, 'and just as I was thinking I should be free of them at last, they must needs come wriggling down from the sky! Ugh, Serpent!'

-- Никакая я не змея! -- сказала Алиса. -- Я просто... просто...

'But I'm NOT a serpent, I tell you!' said Alice. 'I'm a—I'm a—'

-- Ну, скажи, скажи, кто ты такая? -- подхватила Горлица. -- Сразу видно, хочешь что-то выдумать.

'Well! WHAT are you?' said the Pigeon. 'I can see you're trying to invent something!'

-- Я... я... маленькая девочка,---сказала Алиса не очень уверенно, вспомнив, сколько раз она менялась за этот день.

'I—I'm a little girl,' said Alice, rather doubtfully, as she remembered the number of changes she had gone through that day.

-- Ну уж, конечно,--ответила Горлица с величайшим презрением. -- Видала я на своем веку много маленьких девочек, но с такой шеей -- ни одной! Нет, меня не проведешь! Самая настоящая змея -- вот ты кто! Ты мне еще скажешь, что ни разу не пробовала яиц.

'A likely story indeed!' said the Pigeon in a tone of the deepest contempt. 'I've seen a good many little girls in my time, but never ONE with such a neck as that! No, no! You're a serpent; and there's no use denying it. I suppose you'll be telling me next that you never tasted an egg!'

-- Нет, почему же, пробовала, -- отвечала Алиса. (Она всегда говорила правду).--Девочки, знаете, тоже едят яйца.

'I HAVE tasted eggs, certainly,' said Alice, who was a very truthful child; 'but little girls eat eggs quite as much as serpents do, you know.'

-- Не может быть, -- сказала Горлица. -- Но, если это так, тогда они тоже змеи! Больше мне нечего сказать.

'I don't believe it,' said the Pigeon; 'but if they do, why then they're a kind of serpent, that's all I can say.'

Мысль эта так поразила Алису, что она замолчала. А Горлица прибавила: -- Знаю, знаю, ты яйца ищешь! А девочка ты или змея -- мне это безразлично.

This was such a new idea to Alice, that she was quite silent for a minute or two, which gave the Pigeon the opportunity of adding, 'You're looking for eggs, I know THAT well enough; and what does it matter to me whether you're a little girl or a serpent?'

-- Но мне это совсем не безразлично,--поспешила возразить Алиса. -- И, по правде сказать, яйца я не ищу! А даже если б и искала, ваши мне все равно бы не понадобились. Я сырые не люблю!

'It matters a good deal to ME,' said Alice hastily; 'but I'm not looking for eggs, as it happens; and if I was, I shouldn't want YOURS: I don't like them raw.'

-- Ну тогда убирайся! -- сказала хмуро Горлица и снова уселась на свое гнездо. Алиса стала спускаться на землю, что оказалось совсем не просто: шея то и дело запутывалась среди ветвей, так что приходилось останавливаться и вытаскивать ее оттуда. Немного спустя Алиса вспомнила, что все еще держит в руках кусочки гриба, и принялась осторожно, понемножку откусывать сначала от одного, а потом от другого, то вырастая, то уменьшаясь, пока, наконец, не приняла прежнего своего вида.

'Well, be off, then!' said the Pigeon in a sulky tone, as it settled down again into its nest. Alice crouched down among the trees as well as she could, for her neck kept getting entangled among the branches, and every now and then she had to stop and untwist it. After a while she remembered that she still held the pieces of mushroom in her hands, and she set to work very carefully, nibbling first at one and then at the other, and growing sometimes taller and sometimes shorter, until she had succeeded in bringing herself down to her usual height.

Поначалу это показалось ей очень странным, так как она успела уже отвыкнуть от собственного роста, но вскоре она освоилась и начала опять беседовать сама с собой. -- Ну вот, половина задуманного сделана! Как удивительны все эти перемены! Не знаешь, что с тобой будет в следующий миг... Ну ничего, сейчас у меня рост опять прежний. А теперь надо попасть в тот сад. Хотела бы я знать: как это сделать? Тут она вышла на полянку, где стоял маленький домик, не более четырех футов вышиной. -- Кто бы там ни жил, -- подумала Алиса, -- в таком виде мне туда нельзя идти. Перепугаю их до смерти! Она принялась за гриб и не подходила к дому до тех пор, пока не уменьшилась до девяти дюймов.

It was so long since she had been anything near the right size, that it felt quite strange at first; but she got used to it in a few minutes, and began talking to herself, as usual. 'Come, there's half my plan done now! How puzzling all these changes are! I'm never sure what I'm going to be, from one minute to another! However, I've got back to my right size: the next thing is, to get into that beautiful garden—how IS that to be done, I wonder?' As she said this, she came suddenly upon an open place, with a little house in it about four feet high. 'Whoever lives there,' thought Alice, 'it'll never do to come upon them THIS size: why, I should frighten them out of their wits!' So she began nibbling at the righthand bit again, and did not venture to go near the house till she had brought herself down to nine inches high.

Audio from LibreVox.org