Аліса в Країні Чудес

Розділ дванадцятий

CHAPTER XII.

Свідчить Аліса

Alice's Evidence

- Я тут! - гукнула Аліса і, геть забувши, як вона виросла за останні кілька хвилин, підхопилася так рвучко, що подолом спідниці змела з лави всіх присяжних просто на голови публіці. Бідолахи заборсалися на підлозі, наче золоті рибки з акваріума, якого вона перекинула ненароком на минулому тижні.

'Here!' cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of the moment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and she jumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury-box with the edge of her skirt, upsetting all the jurymen on to the heads of the crowd below, and there they lay sprawling about, reminding her very much of a globe of goldfish she had accidentally upset the week before.

- Ой, даруйте - зойкнула перестрашена Аліса й кинулася гарячкове їх підбирати.

Їй і досі не йшов з голови випадок із золотими рибками, і чомусь здавалося, що коли присяжних негайно не позбирати й не посадовити назад, вони неодмінно повмирають.

'Oh, I BEG your pardon!' she exclaimed in a tone of great dismay, and began picking them up again as quickly as she could, for the accident of the goldfish kept running in her head, and she had a vague sort of idea that they must be collected at once and put back into the jury-box, or they would die.

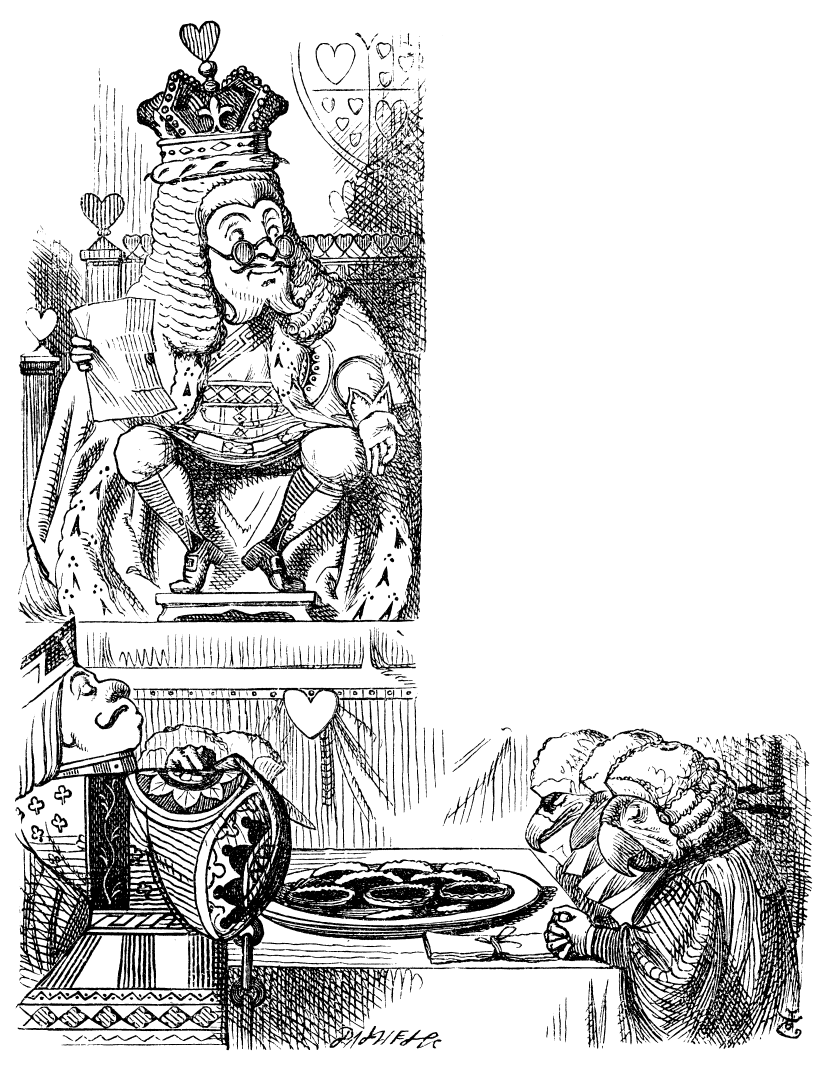

- Суд не продовжить роботи, - оголосив Король замогильним голосом, - доки всі присяжні не будуть на своїх місцях.

- Усі! - повторив він з притиском і блимнув спідлоба на Алісу.

'The trial cannot proceed,' said the King in a very grave voice, 'until all the jurymen are back in their proper places—ALL,' he repeated with great emphasis, looking hard at Alice as he said do.

Аліса глянула на лаву й побачила, що зопалу посадовила Ящура Крутихвоста догори ногами, і тепер бідолаха тільки скорботно помахував хвостиком, неспроможний перевернутися. Вона мерщій вихопила його звідти й посадовила як слід. "А втім, це йому мало допоможе, - сказала вона подумки. - Вниз головою чи вгору - користь однакова".

Alice looked at the jury-box, and saw that, in her haste, she had put the Lizard in head downwards, and the poor little thing was waving its tail about in a melancholy way, being quite unable to move. She soon got it out again, and put it right; 'not that it signifies much,' she said to herself; 'I should think it would be QUITE as much use in the trial one way up as the other.'

Тільки-но присяжні трохи очуняли й повіднаходили свої таблички та пера, вони заходилися завзято писати історію цього нещасливого випадку - всі, окрім Ящура, який, видно, був надто ошелешений, аби щось робити. Він тільки сидів, роззявивши рота і вп'явши очі у стелю.

As soon as the jury had a little recovered from the shock of being upset, and their slates and pencils had been found and handed back to them, they set to work very diligently to write out a history of the accident, all except the Lizard, who seemed too much overcome to do anything but sit with its mouth open, gazing up into the roof of the court.

- Що тобі відомо по суті справи? - звернувся Король до Аліси.

'What do you know about this business?' the King said to Alice.

- Нічого, - відповіла вона.

'Nothing,' said Alice.

- Зовсім нічого? - напосідав Король.

'Nothing WHATEVER?' persisted the King.

- Зовсім, - повторила Аліса.

'Nothing whatever,' said Alice.

- Це дуже важливо! - відзначив Король для присяжних.

Ті вже кинулись були писати, коли це втрутився Білий Кролик.

- Неважливої Ваша величність, звісно, це мали на увазі, чи не так? - проказав він вельми шанобливо, хоч лице йому кривилося в жахливих гримасах.

'That's very important,' the King said, turning to the jury. They were just beginning to write this down on their slates, when the White Rabbit interrupted: 'UNimportant, your Majesty means, of course,' he said in a very respectful tone, but frowning and making faces at him as he spoke.

- Я Неважливо, так, так, звичайно, я це мав на увазі - квапливо поправився Король і забубонів собі під ніс: "Важливо-неважливо, важливо-неважливо..." - мовби пробував на вагу, котре слово краще.

'UNimportant, of course, I meant,' the King hastily said, and went on to himself in an undertone, 'important—unimportant—unimportant—important—' as if he were trying which word sounded best.

Дехто з присяжних записав «важливо», дехто «неважливо». Аліса це дуже добре бачила, бо вже виросла так, що могла легко зазирнути до їхніх табличок. "Але яке це має значення", - вирішила вона про себе.

Some of the jury wrote it down 'important,' and some 'unimportant.' Alice could see this, as she was near enough to look over their slates; 'but it doesn't matter a bit,' she thought to herself.

Зненацька Король, який ось уже кілька хвилин грамузляв щось у записнику, вигукнув:

- Тихо! - і зачитав:

"Закон Сорок другий. Всім особам заввишки в одну милю* і вищим покинути судову залу».

At this moment the King, who had been for some time busily writing in his note-book, cackled out 'Silence!' and read out from his book, 'Rule Forty-two. ALL PERSONS MORE THAN A MILE HIGH TO LEAVE THE COURT.'

Всі прикипіли очима до Аліси.

Everybody looked at Alice.

*0дна миля дорівнює приблизно 1,6 км. - Це я - заввишки в одну милю? - перепитала Аліса.

'I'M not a mile high,' said Alice.

- Так, - сказав Король.

'You are,' said the King.

- А, може, і в дві, - докинула Королева.

'Nearly two miles high,' added the Queen.

- Ну й нехай, але я не вийду, - сказала Аліса. - Тим більше, що це не правильне правило - ви його щойно вигадали.

'Well, I shan't go, at any rate,' said Alice: 'besides, that's not a regular rule: you invented it just now.'

- Це найдавніший закон у записнику, - заперечив Король.

'It's the oldest rule in the book,' said the King.

- Тоді це мав би бути Закон Перший.

'Then it ought to be Number One,' said Alice.

Король зблід і поквапливо згорнув записника.

- Обміркуйте вирок, - тихим тремтячим голосом звернувся він до присяжних.

The King turned pale, and shut his note-book hastily. 'Consider your verdict,' he said to the jury, in a low, trembling voice.

- Даруйте, але це ще не все, ваша величносте, - підскочив до нього Білий Кролик. - Ось письмове свідчення, щойно знайдене.

'There's more evidence to come yet, please your Majesty,' said the White Rabbit, jumping up in a great hurry; 'this paper has just been picked up.'

- І що там? - спитала Королева.

'What's in it?' said the Queen.

- Я ще не дивився, - відповів Кролик, - але, схоже, це лист, написаний підсудним до... до когось.

'I haven't opened it yet,' said the White Rabbit, 'but it seems to be a letter, written by the prisoner to—to somebody.'

- Звичайно, до когось, - озвався Король, - бо писати до нікого було б, знаєте, просто неграмотно.

'It must have been that,' said the King, 'unless it was written to nobody, which isn't usual, you know.'

- А кому він адресований? - запитав один з присяжних.

'Who is it directed to?' said one of the jurymen.

- Нікому. Зверху взагалі нічого не написано, - відповів Кролик, розгортаючи аркуш, і додав:

- Та це ніякий і не лист, це - вірш.

'It isn't directed at all,' said the White Rabbit; 'in fact, there's nothing written on the OUTSIDE.' He unfolded the paper as he spoke, and added 'It isn't a letter, after all: it's a set of verses.'

- Написаний рукою підсудного? - поцікавився інший присяжний.

'Are they in the prisoner's handwriting?' asked another of the jurymen.

- Ні, - відповів Кролик, - і це мене найбільше дивує. (Присяжні спантеличились.)

'No, they're not,' said the White Rabbit, 'and that's the queerest thing about it.' (The jury all looked puzzled.)

- Він, певно, підробив чужу руку, - вирішив Король. (Обличчя присяжних просвітліли.)

'He must have imitated somebody else's hand,' said the King. (The jury all brightened up again.)

- Даруйте, ваша величносте, - озвався Валет, - я вірша не писав, і ніхто цього не доведе: там нема мого підпису.

'Please your Majesty,' said the Knave, 'I didn't write it, and they can't prove I did: there's no name signed at the end.'

- Якщо ти не поставив підпису, - зауважив Король, - то тим гірше для тебе. Без сумніву, ти мав якийсь лихий намір, - інакше підписався б, як усі порядні люди.

'If you didn't sign it,' said the King, 'that only makes the matter worse. You MUST have meant some mischief, or else you'd have signed your name like an honest man.'

Ці слова зняли бурю оплесків: вперше за цілий день Король озвався справді розумним словом.

There was a general clapping of hands at this: it was the first really clever thing the King had said that day.

- Це доводить його провину! - мовила Королева.

'That PROVES his guilt,' said the Queen.

- Нічого це не доводить! - сказала Аліса. - Ви ж навіть не знаєте, про що той вірш.

'It proves nothing of the sort!' said Alice. 'Why, you don't even know what they're about!'

- Читай вірша! - звелів Король.

'Read them,' said the King.

Білий Кролик надяг окуляри.

- Звідки починати, ваша величносте? - запитав він.

The White Rabbit put on his spectacles. 'Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?' he asked.

- З початку, - глибокодумно відповів Король, - і читай до кінця. А тоді - закінчуй.

'Begin at the beginning,' the King said gravely, 'and go on till you come to the end: then stop.'

І Білий Кролик прочитав такого вірша:

These were the verses the White Rabbit read:—

Я знаю від них, що ви в неї були

Й сказали про всіх навпростець.

Вважає вона, що я гідний хвали,

з мене поганий плавець.

'They told me you had been to her,

And mentioned me to him:

She gave me a good character,

But said I could not swim.

Він їм передав, що я не пішов

(Ми знаємо, звідки й куди):

Якщо вона справу порушить ізнов,

То вам не минути біди.

He sent them word I had not gone

(We know it to be true):

If she should push the matter on,

What would become of you?

Я дав їй один, вона йому - два,

А ви нам, здається, три.

Та всі повернулись від нього до вас.

Все ясно: крути - не крути.

I gave her one, they gave him two,

You gave us three or more;

They all returned from him to you,

Though they were mine before.

Коли ж доведеться мені чи їй

Відповідати за те,

Він вірить, що ви їх, як нас колись,

воленьку віддасте.

If I or she should chance to be

Involved in this affair,

He trusts to you to set them free,

Exactly as we were.

Ще доки на неї дур не найшов,

ви в понятті моїм

муром, який недоречно зійшов

Між нами, між ними й між ним.

My notion was that you had been

(Before she had this fit)

An obstacle that came between

Him, and ourselves, and it.

Що їй вони любі - йому не кажіть,

(Ціну треба знати словам):

До вічного віку секрет бережіть,

Мені лиш відомий та вам.

Don't let him know she liked them best,

For this must ever be

A secret, kept from all the rest,

Between yourself and me.'

- Це найважливіше свідчення, яке ми сьогодні чули, - потер руки Король. - Отож нехай присяжні...

'That's the most important piece of evidence we've heard yet,' said the King, rubbing his hands; 'so now let the jury—'

- Якщо хтось із них розтлумачить цей вірш, - перебила його Аліса (за останні хвилини вона так виросла, що вже анітрохи не боялася перебити Короля), - я дам йому шість пенсів. Я не бачу в ньому ані крихти глузду!

'If any one of them can explain it,' said Alice, (she had grown so large in the last few minutes that she wasn't a bit afraid of interrupting him,) 'I'll give him sixpence. I don't believe there's an atom of meaning in it.'

Присяжні занотували в табличках: «Вона не бачить у ньому ані крихти глузду», - але розтлумачити вірш не зохотився ніхто.

The jury all wrote down on their slates, 'SHE doesn't believe there's an atom of meaning in it,' but none of them attempted to explain the paper.

- Якщо у вірші нема глузду, - сказав Король, - то нам і гора з пліч, бо тоді не треба його й шукати.

Він розправив аркуш на коліні і, заглядаючи туди одним оком, додав:

- А втім, а втім... Певний глузд, бачиться, тут усе-таки є... «Хоч з мене поганий плавець»?.. Ти теж чомусь не любиш плавати, га? - звернувся він до Валета.

'If there's no meaning in it,' said the King, 'that saves a world of trouble, you know, as we needn't try to find any. And yet I don't know,' he went on, spreading out the verses on his knee, and looking at them with one eye; 'I seem to see some meaning in them, after all. "—SAID I COULD NOT SWIM—" you can't swim, can you?' he added, turning to the Knave.

Валет сумно похитав головою.

- Хіба по мені видно? - запитав він. (Не видно було б хіба сліпому - він був картонний.)

The Knave shook his head sadly. 'Do I look like it?' he said. (Which he certainly did NOT, being made entirely of cardboard.)

- Поки що сходиться, - сказав Король і далі забурмотів. - «Ми знаємо, звідки й куди...» - це, звісно, стосується присяжних... «Я дав їй один, вона йому - два» - то ось що він робив із пиріжками!..

'All right, so far,' said the King, and he went on muttering over the verses to himself: '"WE KNOW IT TO BE TRUE—" that's the jury, of course—"I GAVE HER ONE, THEY GAVE HIM TWO—" why, that must be what he did with the tarts, you know—'

- Але далі сказано: «Та всі повернулись від нього до вас», - зауважила Аліса.

'But, it goes on "THEY ALL RETURNED FROM HIM TO YOU,"' said Alice.

- Певно, що повернулись! - тріумфально вигукнув Король, показуючи на таріль з пиріжками. - «Все ясно, крути - не крути...»

- А далі це: «Ще доки на неї дур не найшов...» На тебе ж, любонько, здається, ніколи дур не находить? - звернувся він до Королеви.

'Why, there they are!' said the King triumphantly, pointing to the tarts on the table. 'Nothing can be clearer than THAT. Then again—"BEFORE SHE HAD THIS FIT—" you never had fits, my dear, I think?' he said to the Queen.

- Ніколи! - ревнула Королева й пожбурила чорнильницею в Ящура.

(Горопашний Крутихвіст облишив був писати пальцем, побачивши, що це марна трата часу, але тепер, коли чорнило патьоками стікало йому по обличчю, почав підставляти пальця під нього і знову гарячково водив ним по табличці.)

'Never!' said the Queen furiously, throwing an inkstand at the Lizard as she spoke. (The unfortunate little Bill had left off writing on his slate with one finger, as he found it made no mark; but he now hastily began again, using the ink, that was trickling down his face, as long as it lasted.)

- Правда, не находить? - перепитав Король, лукаво мружачи очі.

- Ні! Ні! - затупотіла ногами Королева.

- Тоді суддя тут правди не знаходить, - сказав Король, з усміхом обводячи очима залу.

Запала гробова тиша.

'Then the words don't FIT you,' said the King, looking round the court with a smile. There was a dead silence.

- Це каламбур, - ображено додав він, і всі засміялися.

- Нехай присяжні обміркують вирок, - повторив Король уже чи не вдвадцяте за день.

'It's a pun!' the King added in an offended tone, and everybody laughed, 'Let the jury consider their verdict,' the King said, for about the twentieth time that day.

- Ні, ні! - урвала Королева. - Спершу страта, а тоді вирок!

'No, no!' said the Queen. 'Sentence first—verdict afterwards.'

- Нісенітниця! - голосно вигукнула Аліса. - Як могло вам таке прийти в голову!

'Stuff and nonsense!' said Alice loudly. 'The idea of having the sentence first!'

- Замовкни! - крикнула Королева, буряковіючи.

'Hold your tongue!' said the Queen, turning purple.

- Не замовкну! - відповіла Аліса.

'I won't!' said Alice.

- Відтяти їй голову! - вереснула Королева.

Ніхто не ворухнувся.

'Off with her head!' the Queen shouted at the top of her voice. Nobody moved.

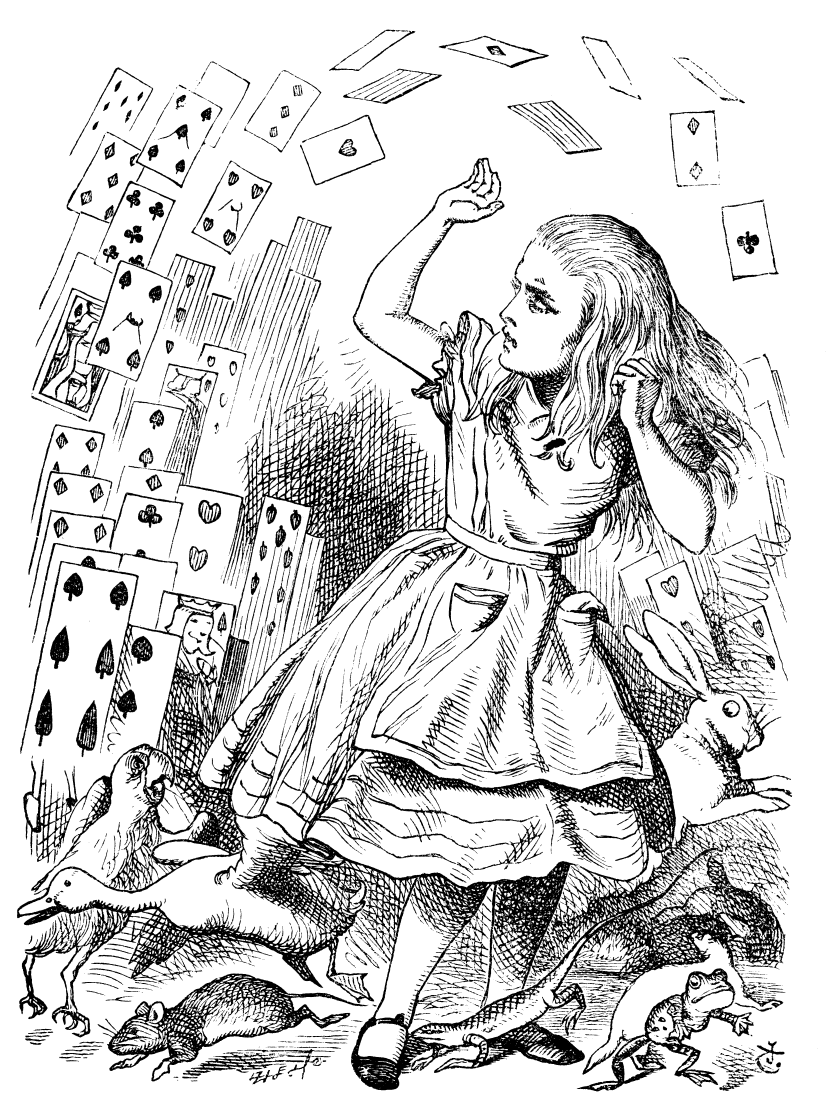

- Та хто вас боїться! - сказала Аліса, яка на той час уже виросла до своїх звичних розмірів. - Ви ж просто колода карт!

'Who cares for you?' said Alice, (she had grown to her full size by this time.) 'You're nothing but a pack of cards!'

Тут раптом усі карти знялися в повітря й ринули на неї. Аліса ойкнула - чи то з переляку, чи спересердя, - почала від них відбиватися і... побачила, що лежить на березі, поклавши голову сестрі на коліна, а та обережно змахує їй з обличчя сухі листочки, звіяні вітром з найближчого дерева.

At this the whole pack rose up into the air, and came flying down upon her: she gave a little scream, half of fright and half of anger, and tried to beat them off, and found herself lying on the bank, with her head in the lap of her sister, who was gently brushing away some dead leaves that had fluttered down from the trees upon her face.

- Алісо, люба, прокинься! - сказала сестра. - Та й довго ж ти спала!

'Wake up, Alice dear!' said her sister; 'Why, what a long sleep you've had!'

- Зате який дивний сон я бачила! - сказала Аліса і стала переповідати все-все, що їй запам'яталося з незвичайних пригод, про які ти щойно прочитав.

Коли вона скінчила, сестра поцілувала її, мовивши:

- Що й казати, моє золотко, сон і справді дивний. Але вже вечоріє - біжи-но пити чай.

Аліса підвелася і щодуху побігла додому, не перестаючи дивуватися, який же чудовий їй наснився сон.

'Oh, I've had such a curious dream!' said Alice, and she told her sister, as well as she could remember them, all these strange Adventures of hers that you have just been reading about; and when she had finished, her sister kissed her, and said, 'It WAS a curious dream, dear, certainly: but now run in to your tea; it's getting late.' So Alice got up and ran off, thinking while she ran, as well she might, what a wonderful dream it had been.

А сестра так і залишилася сидіти, підперши голову рукою. Вона дивилася, як сідає сонце, і думала про малу Алісу, про всі її дивовижні пригоди, аж поки й сама не поринула в сон...

But her sister sat still just as she left her, leaning her head on her hand, watching the setting sun, and thinking of little Alice and all her wonderful Adventures, till she too began dreaming after a fashion, and this was her dream:—

І найперше наснилася їй сама Аліса: тендітні руки малої знов обплели її коліна, а ясні, жваві оченята заглядали їй у вічі... Вона чула всі відтінки її голосу, бачила, як Аліса звично стріпує головою, відкидаючи непокірні пасма волосся, що вічно спадали їй на очі. І доки вона отак уважно слухала (так їй, принаймні, здавалося), все довкола стало оживати й повнитися чудернацькими істотами з Алісиного сну...

First, she dreamed of little Alice herself, and once again the tiny hands were clasped upon her knee, and the bright eager eyes were looking up into hers—she could hear the very tones of her voice, and see that queer little toss of her head to keep back the wandering hair that WOULD always get into her eyes—and still as she listened, or seemed to listen, the whole place around her became alive with the strange creatures of her little sister's dream.

Ось пробіг Білий Кролик, шелеснувши високою травою біля самих її ніг... десь у сусідньому ставку захлюпотілася, тікаючи, нажахана Миша... чутно було, як дзенькають чашки на нескінченній гостині Шаленого Зайця та його приятелів... як пронизливо верещить Королева, посилаючи на страту своїх безталанних гостей... і знов дитина-порося чхала на колінах у Герцогині, а довкола брязкали тарілки та полумиски... знову в повітрі чувся Грифонів крик, порипування Ящурового пера та кректання придушених морських свинок, зливаючись із далекими схлипами горопашного Казна-Що-Не-Черепахи...

The long grass rustled at her feet as the White Rabbit hurried by—the frightened Mouse splashed his way through the neighbouring pool—she could hear the rattle of the teacups as the March Hare and his friends shared their never-ending meal, and the shrill voice of the Queen ordering off her unfortunate guests to execution—once more the pig-baby was sneezing on the Duchess's knee, while plates and dishes crashed around it—once more the shriek of the Gryphon, the squeaking of the Lizard's slate-pencil, and the choking of the suppressed guinea-pigs, filled the air, mixed up with the distant sobs of the miserable Mock Turtle.

Отак сиділа вона, приплющивши очі, й майже вірила у країну чудес, хоча знала, що досить їх розплющити, і все знову стане цілком звичайним: то просто вітер шелестітиме травою, і під його подмухами братиметься жмурами й шарудітиме очеретами сусідній став; дзенькіт чашок стане дзеленчанням дзвіночків на шиях овець, а верески Королеви - голосом вівчарика; чхання немовляти, Грифонів крик та решта чудних звуків зіллються в гармидер селянської господи, а далеке мукання корів заступить тяжкі схлипи Казна-Що-Не-Черепахи...

So she sat on, with closed eyes, and half believed herself in Wonderland, though she knew she had but to open them again, and all would change to dull reality—the grass would be only rustling in the wind, and the pool rippling to the waving of the reeds—the rattling teacups would change to tinkling sheep-bells, and the Queen's shrill cries to the voice of the shepherd boy—and the sneeze of the baby, the shriek of the Gryphon, and all the other queer noises, would change (she knew) to the confused clamour of the busy farm-yard—while the lowing of the cattle in the distance would take the place of the Mock Turtle's heavy sobs.

А далі вона уявила собі, як її мала сестричка стане колись дорослою жінкою і, зберігши до зрілих літ щире й лагідне дитяче серце, збере довкола себе інших дітей і засвічуватиме їм оченята своїми незвичайними оповідями. Можливо, розповідатиме вона їм і про Країну Чудес, що наснилася їй багато років тому; вона перейматиметься їхніми нехитрими жалями і простими радощами, пам'ятаючи своє власне дитинство і щасливі літні дні...

Lastly, she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and how she would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood: and how she would gather about her other little children, and make THEIR eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of Wonderland of long ago: and how she would feel with all their simple sorrows, and find a pleasure in all their simple joys, remembering her own child-life, and the happy summer days.

THE END

Audio from LibreVox.org